![]() QUESTION:

QUESTION:

I have an old fashion balance scale, center fulcrum and two dishes on either side of equal weight. If I place two weights on either side and the weights are nearly the same, the heavier side dips slightly, if the difference between the weights are large, the heavier side dips much more. I do not understand why this is so. Logic says that if there is any difference at all, the heavier side should continue to drop until it reaches a barrier to the fall no matter what the difference in the weight.

I asked a physics instructor and he did not have the answer either.

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

I have received this question before and, alas, I have not found

the answer. I have asked readers to suggest answers but nobody ever has.

See an earlier answer.

![]() ADDED

ANSWER:

ADDED

ANSWER:

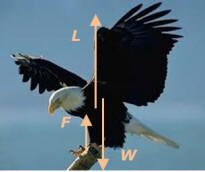

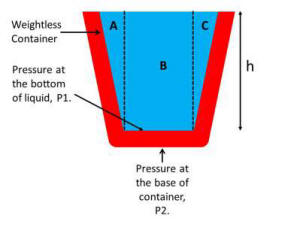

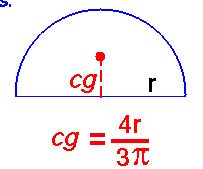

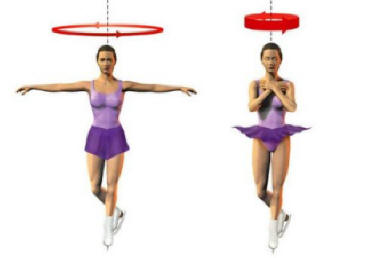

I have found the answer. The center of mass

⊗ of the scale

itself must be below the fulcrum (suspension point). Then, as shown

above, if the beam is off horizontal for the empty scale or equal

weights in each pan, there will be a restoring torque to force a balance

only for the horizontal beam.

![]() QUESTION:

QUESTION:

I made a statement to somebody that a plane hitting a building was the same as if the building hit the plane at exactly the same speed,the plane now stationary. The results would be the same. In other words, if a man with large hands slapped my hand at 50 mph, it would be same as me slapping his hand at 50 mph.....its interchangable.....the other person said, no, the mass of the building and hand would have different results...

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

Either you or your friend could be right depending on what you

mean by "different results". Let me try to set up a simple example to

demonstrate why.

-

Imagine we have a 2 lb ball of putty moving with a speed of 5 mph striking and sticking to a 18 lb bowling ball at rest; the time it takes to collide is 0.1 s. After the collision, the two move together with a speed of v1. To find v1, use momentum conservation: 2x5=(18+2)v1, v1=0.5 mph.

-

Next, imagine we have a 18 lb bowling ball moving with a speed of 5 mph striking and sticking to a 2 lb ball of putty at rest; the time it takes to collide is 0.1 s. After the collision, the two move together with a speed of v2. To find v2, use momentum conservation: 18x5=(18+2)v2, v2=4.5 mph.

So, you see that the two scenarios have different speeds after the colliision. But, suppose that you were the putty ball. During the collision you feel a force and the force is what is going to hurt you. Do you get hurt as badly, not as badly, or equally as badly during the collision? What determines the force you feel is the acceleration you experience during the collision, how quickly your velocity changes, which is your final velocity minus your initial velocity divided by the time of the collision.

-

For the putty ball moving initially, (vfinal-vinitial)/t=(0.5-5)/0.1=-45 mph/s.

-

For the bowling ball moving initially, (vfinal-vinitial)/t=(0-4.5)/0.1=-45 mph/s.

You could go through through the exact same process to find that the bowling ball experienced exactly the same force regardless of who moved initially. A physicist would say that you were right, but the ambiguity of your statement means that the other guy could split hairs. As far as physics is concerned, the only thing which matters is the relative velocities of the two before the collision. If the putty ball were moving 105 mph and the bowling ball were moving 100 mph in the same direction, the result of the collision which matters (the force) would be the same.

![]() QUESTION:

QUESTION:

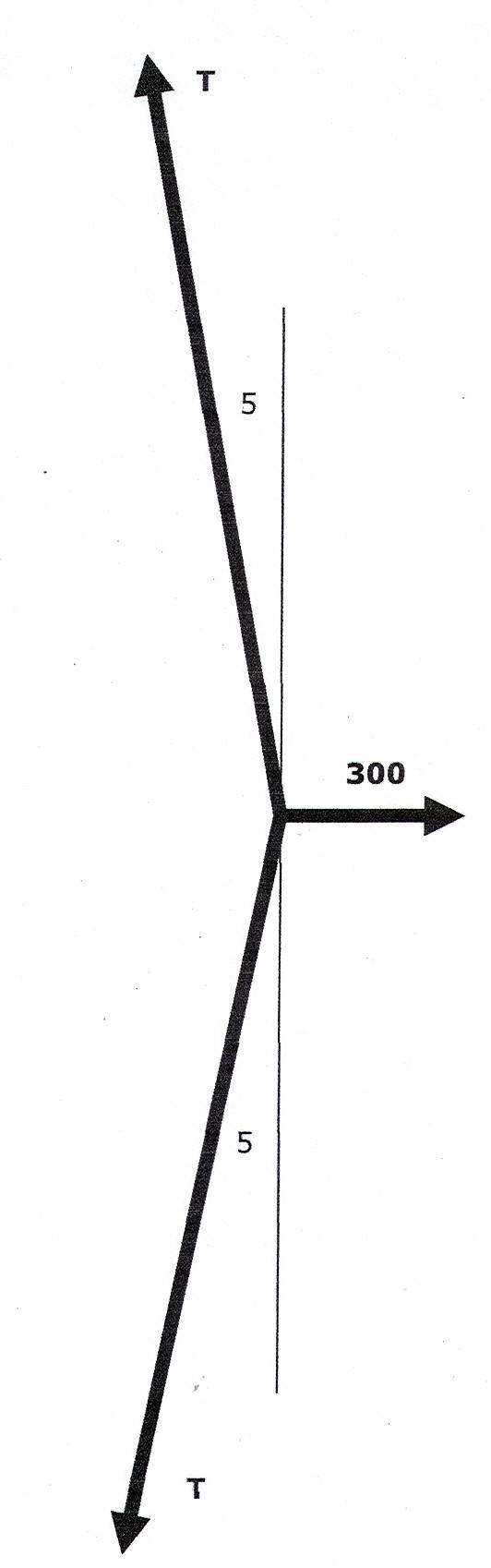

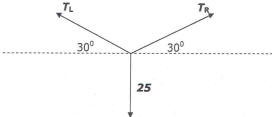

My question is about the maximum tension experienced by a bow string. I'm

specifically concerned with a traditional or recurve bow NOT a compound bow

with pullies. I want to know the max tension compared to the draw weight so

I have an idea how strong to make my strings. So here's the scenario, what's

the maximum tension in the string for a recurve with a 70 lbs draw weight

and a physical weight of 25 oz? I'm assuming the maximum tension is when

it's at brace (not full draw), right after the arrow leaves. I think this

because not only does the string have to oppose the restoring force of the

bow limbs but it also has to stop the momentum of the limbs that isn't

transferred to the arrow.

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

To compute the tension I would need to know the geometry of the bow. I can

tell you that the tension will be at the maximum draw for a simple bow, not

where the arrow leaves the string.

![]() REPLY:

REPLY:

The bow is 64 inches long and the string is about 4-5 inches shorter than the bow. It Is braced at 6 inches and has tips that are 3 inches recurved behind the handle. Its draw length is 28 inches and has an elipitcal/circular tiller shape at full draw.

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

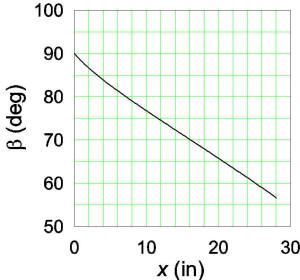

(An incorrect answer was posted earlier. This is a reposting, correct

now, I hope!)

When researching the physics of archery I discovered that this can be a

very complicated problem requiring very sophisticated numerical

calculations on computers if you want precision descriptions of all the

details. You, however, require only a rough calculation for estimating

the strength of the string. I can do that and it is more appropriate for

the spirit of this site‚ÄĒto solve problems with simple physics

concepts. This problem requires facility with trigonometry,

understanding of Hooke's law, and application of Newton's first law. The

simple model I will use was one used before the advent of computers; the

bow is modeled as two straight rods (purple) the ends of which move on a

circle as the string (red) is drawn. With this simple model, most of the

details of your bow are not necessary. When the string is braced

(undrawn) there is a certain tension in the string and this tension will

increase as the bow is drawn. So, the maximum will be at the maximum

draw. The figure shows, roughly to scale, the situation. Using simple

trigonometry (law of cosines), I find β=59.60.

The point where the draw weight W is being applied must be in

equilibrium, W-2Tcosβ=0; solving, T=69.2

lb. I think that your concern about the string having to "stop the

momentum of the limbs" is misplaced because bows tend to be quite

elastic so that nearly all the energy imparted to the bow by drawing it

is imparted to the arrow and the limbs will end nearly at rest. Not so

if you draw and release without an arrow, though; what I have read is

that in that situation you are more likely to break your bow than the

string. I am working on a general solution which I will later add here

but thought I would post the part of the solution which answers your

question regarding the tension in the string.

![]() GENERALIZED

SOLUTION:

GENERALIZED

SOLUTION:

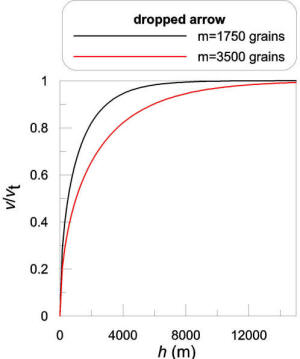

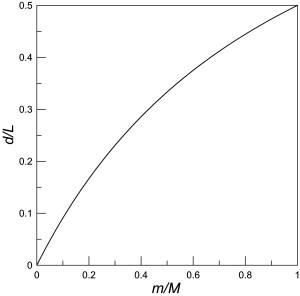

To get a better understanding of this problem it is worthwhile to

find an analytical solution for the tension as a function of draw

distance. My research showed me that a traditional or recurve bow

behaves, to an excellent approximation, like a simple spring

(Hooke's law), the draw weight being proportional to the draw distance,

i.e. W≈kx where x is the distance the

string is drawn and k is the spring constant. In this case, since W=70 lb when x=28

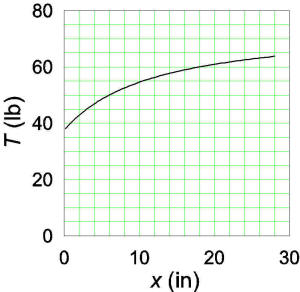

in, k=2.5 lb/in. Using the law of cosines, cosβ=(L2+(x+d)2-R2)/(2L(x+d)).

Again, the point where the force W is applied

is in equilibrium so W-2Tcosβ=0 or T(x)=kx/(2cosβ).

Now, note that in the limit where x → 0, β → 900

and cosβ → x/L. Therefore T(0)=kL/2.

Using your numbers, T(0)=37.5 lb and the angle and tension for

all points are plotted below. At full draw, β=560

and T=64 lb. It was interesting to me that in order for the

calculated values to be correct at zero draw, very precise relative values of

R and L

had to be used because otherwise the expression for cosβ would not be 0 exactly when x=0. The value was

R=30.59411708 inches for L=30.

![]() QUESTION:

QUESTION:

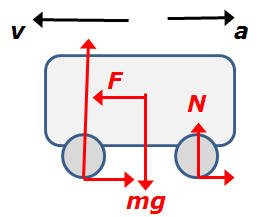

Suppose a block is moving with constant velocity towards right on a frictionless surface and during its motion another block of slightly smaller mass lands on top of it from a negligible height.

I argue that the lower block will eventually start moving to the left and upper block will end up moving towards right provided that there is friction between the blocks but not between lower block and ground . My friends can't accept my reasoning. Am I wrong? Please help!

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

I hate to tell you, but you are wrong. This is actually a simple

momentum conservation problem. Call the masses of the upper and lower

blocks m and M, respectively. Before they come

together the momentum is Mv where v is the incoming

speed of M. When the masses come in contact they will slide on

each other but, because there is friction, they will eventually stop

sliding and both will move with a velocity u; the linear momentum will

now be (M+m)u. Conserving momentum, u=[M/(M+m)]v.

They both end up going with speed u and move to the right.

You can also determine the time it takes for the sliding to stop. m will feel a frictional force to the right of magnitude f=μmg and M will feel a frictional force to the left of magnitude f=μmg (Newton's third law). So, choosing +x to the right, the acceleration of m is a=μg and the acceleration of M is A=-μg(m/M). The velocities as a function of t are vm=μgt and vM=v-μgt(m/M); we are interested in the time when vm=vM, so solving for t, t=Mv/[μg(M+m)]. If you substitute this back into vm or vM, you will find the same value we found for u above: vm=vM=u=[M/(M+m)]v.

![]() FOLLOWUP QUESTION:

FOLLOWUP QUESTION:

If the block of mass M is not too long, i.e., the total distance that the upper block can slide is less that the distance it could move in your calculated time " t" , wouldn't the two blocks get separated?

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

Well, of course the block has to be big enough, otherwise m

will drop down on the frictionless surface. It would be a good exercize

for a student to calculate how far the block would slide for some

μ. And then, if this is greater than the size of the bottom

block, how fast will each be moving after separating.

![]() QUESTION:

QUESTION:

I do not want a theoretical answer, but has any experimentalist ever put a very sensitive weight balance below a vacuum chamber before and after vacuating it? Does it get lighter or... heavier? I do not have a sensitive balance nor a vacuum chamber.

The reason I ask is that it would say something about the density, or absence of density, of the vacuum.

If I understand pressure correctly, the scale would read a smaller weight value, due to less gas being in the column of air directly above it, but there might also be new physics there, if it is not the case. I simply do not know.

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

You do not want a "theoretical answer" but you clearly do not understand

the physics so I am obliged to give you one anyway. Let us assume the

simplest possible "weight balance" so that I do not have to worry that

it might operate differently in a vacuum. Envision just a simple string

with a tiny butcher's scale which will measure the tension in the string

and then hang an unknown weight of mass M and volume V

from the string. Besides the string, there are two forces on the object

being weighed, its weight Mg and the buoyant force B=ρVg

where ρ is the density of air (about 1 kg/m3 at

atmospheric pressure) and g=9.8 m/s2 is the

acceleration due to gravity. The scale will read W=Mg-B, an

incorrect measure of the weight. Putting the whole device in a vacuum

will change B to zero because the air is gone, so W=Mg,

the correct weight. To get an idea of how important this is, consider

weighing a solid block of iron whose mass is 1 kg. The density of iron

is ρiron=7870 kg=M/V, so the

volume of the block is V=1/7870=1.27x10-4 m3.

So, the true weight is W=9.8 N and the measured weight in air

is (9.8-1.27x10-4) N=9.7999 N, an error of 0.0013%. However,

there are certainly examples where the effect of buoyancy would be very

important. For example, consider an air-filled balloon. I did a rough

calculation and estimated that the volume of an inflated balloon is

about 5x10-3 m3 so it contains about 5x10-3

kg of air; the mass of an uninflated balloon is about 5 gm=5x10-3

kg, so the total weight of the inflated balloon is about 9.8x10-2

N. But if you weighed it in air you would only measure half that amount.

Your question, has anybody ever actually observed this, is a no brainer:

since the existence of a buoyant force has been known and understood for

well over 2000 years (Archimedes' principle), anyone wanting to make an

extremely accurate measurement of a mass would either correct for it or

eliminate it.

![]() QUESTION:

QUESTION:

Several years ago, I was caught in a massive windstorm in a skyscraper. I was on the 54th floor (approx. 756 feet from street level, full building height is 909 feet) , pulling cable, and I stopped for a break. I left a cable pulling string hanging from the ceiling (48 inches free hanging length) in the office, with a 1/4 lb weight attached, and when the storm hit, the weight began swinging like a pendulum. The arc was 16 inches (eyeballing it), and traversing the length of the arc took about 1 second. How can I calculate how far (full arc) the skyscraper was moving by observing what the pendulum in the building was doing?

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

A 48" pendulum has a period of about 2.2 s, the time to swing over the

arc and back. Since you were estimating, the pendulum was swinging with

about the period it would if the building were not moving at all. I

would conclude that either the pendulum got swinging somehow and the

building was not perceptibly moving or that the period of the building's

motion was about the same. If the building was swinging with a period

significantly different from 2 s, the pendulum would be swinging with

that same period; that is called a driven oscillator.

![]() QUESTION:

QUESTION:

Let's say you have three 20-foot putts. Same stimp meter (pace on the green). Let's say in all cases, the green is flat after the hole. I.e. don't worry about things like the ball running away or anything.

-

Putt 1 travels flat and then shortly before the hole, it rises 6 inches.

-

Putt 2 has an rise of 6 inches right after you hit it, and then travels flat to the hole the rest of the way.

-

Putt 3 rises 6 inches gently from the ball to the hole at a constant angle.

Do you hit all three putts the same initial speed? Follow up question : What if you have the same 20 foot putt but halfway to the hole the ground rises 8 inches, and then drops 2 inches and then flattens out the rest of the way to the hole. . .same speed?

![]() ANSWER:

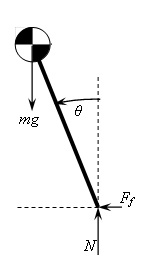

ANSWER:

Refer to the figure.

If there were no friction, it would make no difference how the rise

occurred, only the amount of rise. In that case vhole=√(vputt2-2gh).

However, there is friction which will slow the ball further and the

frictional force on a slope (f=μmgcosθ) will

be different than on level ground (f=μmg); here μ

is the coefficient of friction (essentially, I believe, what is

measured by the "stimp meter"), m is the mass of the ball, and

g is the acceleration due to gravity. Since the frictional

force is smaller on the slope, you might think that less energy is lost

to friction on the slope. But, what matters is not the force but its

product with the distance s over which it acts, specifically

the work done by friction is Wf=-fs where

the negative sign indicates that the friction takes energy away from the

ball. When the ball is moving forward along along the segment L2,

the distance it travels is s=L2/cosθ

and so the work done is Wf=fs=(μmgcosθ)(L2/cosθ)=μmgL2,

exactly the same as if the slope was not there. The total work done by

friction, regardless of the path, is Wf=μmgL.

The final velocity is then

vhole=√[vputt2-2g(h+μL)].

![]() QUESTION:

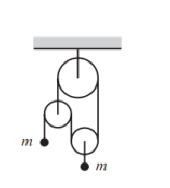

QUESTION:

I'm coordinating a piece of action for a tvc (tv ad), which requires me to build a rig to raise an actor 3 m off the ground, as if he is being taken away by aliens! It's been a long time since school for me, however I feel that there would be a formula that would assist me in calculating how much counterweight is required on a pulley system with 2:1 MA to raise an 80kg actor 3m in 1.5 seconds?

Are you able to clarify the principals to be used in calculating this problem?

This is definitely not homework!

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

The actor will experience an accelleration a such that he moves a

distance y in a time t: y=½at2

, so for this case a=2y/t2=2x3/(1.5)=2.7

m/s2. Choosing the man plus pulley above him as the body

(assuming the mass of the pulley is negligible), Newton's second law is

2T-mg=ma or T=½m(g+a)=½x80x(9.8+2.7)=500

N where g=9.8 m/s2 is the acceleration due to

gravity. Finally sum forces for the weight Mg which has the

same magnitude of acceleration as the actor: Mg-T=Ma, so

M=T/(g-a)=500/(9.8-2.7)=70.4 kg. You may want to keep in

mind that the speed of the actor at the end of the 1.5 s is v=at=2.7x1.5=4.05

m/s; if the weight is stopped after the 1.5 s, he will continue moving

upwards until he has risen another h=½v2/g=0.84

m and then fall back.

![]() QUESTION:

QUESTION:

I've been trying to figure out how to weigh my boat on its trailer, and it seemed to me that putting a scale under each of the two wheels and the tongue and adding the three weights together might not yield a correct result, but your

table weight answer, makes me think maybe it could be.

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

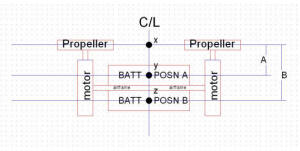

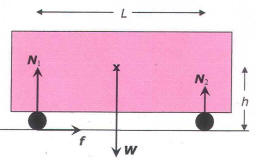

Assuming that you do not have three scales which could be all engaged at

once, lifting one wheel at a time will introduce errors. Refer to the figure above

(noting that I have made the boat on the trailer invisible!): I have

notated 2S as the distance between the wheels, L the

distance from the axle to the tongue support, q the distance

from the ground to the center of mass (COM

©) of the boat plus trailer, d

the distance of COM forward of the axle, and W the weight of

the boat plus trailer. The normal forces Ni

are the forces up on each of the three points of contact; if an ideal

scale of zero thickness were placed under a wheel, the magnitude of the

appropriate normal force is what it would read and N1+N2+N3=W. I have also assumed that the

COM is centered laterally. The geometry and algebra are a bit tedious,

so I give only final answers. In each case I imagine lifting one point

of contact by the angle θ and then measuring the normal

force which I will call N'i. N'3

is the easiest since it does not depend on θ, N'3=Wd/L.

The other two are, by symmetry, the same: N'1=N'2=½W[1-(d/L)-(½q/S)tanθ].

If you now compute the sum, N'1+N'2+N'3≡W'=W[1-(q/S)tanθ].

So your measurement of the weight will be wrong. As an example, suppose

that S=3 ft and q=5 ft and you lift a wheel h=4

in=1/3 ft off the ground; then tanθ=(1/3)/(2x3)=1/18 and

the measured weight will be W(1-(5/3)/18)=0.91W,

nearly a 10% error. The culprit here is that the center of gravity is so

far off the ground. To get a more accurate measurement, block the

opposite wheel so that it is also h above the ground (the

tongue support does not need to be blocked); you only have to do this

once since N1=N2 and N3

does not depend on its height.

![]() FOLLOWUP QUESTION:

FOLLOWUP QUESTION:

Also, in your

table weight example, wouldn't elevating one end of the table with a 2x4 and putting a scale beneath it shift (rotate) the table's weight (CoG) somewhat toward its other end and lessen the measured weight of the weighed end, and error be particularly noticeable if the span of the table is short and the scale is several inches high? If I could remember my trig I could pose this question more intelligently, but the extreme, if hypothetical, case would be if the table end were elevated all the way to vertical, where it would weigh nothing.

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

Congratulations, you have caught one of The Physicist's rare

errors! I must admit that I was thinking small angle here and that is

the only case where it is a good approximation to say that elevating one

end of the table does not change the normal force. And, again, I did not

really appreciate the importance of the fact that the COM is not

colinear with the other two forces until I started puzzling over your

boat trailer question. You can see an example of a case where this is

not an issue in an earlier question about a

boat dock. The correct

answer to the

table weight

example would be W'=W[1-(q/S)tanθ].

(I have changed the notation and assumptions from original problem just

to make the solution more concise. In particular, I have assumed that

the COM is a distance q above the floor and equidistant from

the ends and sides; I have neglected the weight w of the 2x4,

and ¬ĹW=W1=W2; S

is the length of the table.) So, if q=3 ft, S=10 ft,

and h=1/3 ft (COM above floor), W'=W[1-(3/10)(1/3)/10]=0.91W.

![]() QUESTION:

QUESTION:

I would like to know the formula to calculate the final speed of a

mass sliding down a steep slope and hitting a less steep slope to the bottom.

Obviously I cannot calculate the speed on each slope separately and

add them. Here are the numbers.

-

First slope : 1.721 Meter high, 35 degrees, friction coefficient 0.14.

-

Second slope : 2.536 Meter high, 25 degrees, friction coefficient 0.14.

Obviously the final speed will not be the total of both speeds, so how do I add the speed of the first slope to the second slope to obtain final velocity?

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

Well, I started to work this out and found that the length of the two

runs are exactly 3 m and 6 m. I therefore surmise that this is

homework and this site is not for homework help.

![]() FOLLOWUP QUESTION:

FOLLOWUP QUESTION:

Hahaha, thank you for answering. At 51, I am surely not going back to school :) In fact the lenght I gave you are not precisely the one I will use for the slides. I want to understand the way to make the right calculations because the first incline has to be steeper to reduce the overall length of the slide. I am a conceptor mostly in transportation but this project is for a waterpark.

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

It is easiest to do this using energy concepts. Total energy of a mass

m moving with speed v and at a height h above

some arbitrarily chosen h=0 level is E=½mv2+mgh;

g=9.8 m/s2 is the acceleration due to gravity. For a

given system the energy is conserved (the same everywhere) as long as

there is no agent adding or subtracting energy from the system. If there

were no friction in your slides, energy would be conserved. so, if you

chose h=0 at the bottom and started from the top with v=0,

the initial energy would be E1=mgh and the

final energy would be E2=½mv2;

setting them equal and solving for v, v=√(2gh);

note that the mass does not matter. In your case, v=√(2x9.8x(1.721+2.536))=9.13

m/s.

Alas, there is friction and the frictional force f for a mass m sliding on an incline θ is f=μmgcosθ. The amount which a force changes the energy if it acts over a distance s is called the work done and the work done by friction is Wf=-μmgs·cosθ; the minus sign indicates that friction takes energy away from the system. Now, instead of writing E2=E1, we write E2=E1+W—the energy you end up with equals the energy you started with plus what you added (negative for the case of friction).

Now we can address your specific case. ½mv2=mgh-μmgs1cosθ1-μmgs2cosθ2=9.8x[(1.721+2.536)-0.14(3cos350+6cos250)]=31.6 m2/s2. Solving for the velocity, v=7.95 m/s.

The formula you seek if you are doing a slide with two different slopes is v=√{2g[h-μ(s1cosθ1+s2cosθ2)]}.

![]() QUESTION:

QUESTION:

I was asked by my son if you get more speed on a flat (fixed slope) skate ramp or a curved ramp (1/4 pipe) of equal height (12ft). I think the flat ramp would result in greater speed as there is no change in energy force and the fixed straight ramp is constant, the 1/4 pipe is vertical and needs to change direction to horizontal resulting in directional change and loss of energy

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

Your reference to "change in energy

force" has no meaning in physics. If friction is neglected, the only

thing which matters is the vertical distance fallen and so the speed at

the bottom would be identically the same regardless of the shape of the

ramp. Refer to the figures on the left. Without friction, the speed at

the bottom is v=√(2gh) where h is the

height. Including friction complicates things.

-

The ramp is easiest to do: the three forces on the skater are his weight mg, the normal force N, and the frictional force f. The magnitude of the frictional force is f=μN where μ is the coefficient of friction. Newton's equations are ΣFy=N-mgcosφ=0 and ΣFx=mgsinφ-μN=ma; the solutions are N=mgcosφ and a=g(sinφ-μcosφ). Now, notice that the acceleration depends on the angle of the incline which means that the speed at the bottom will also depend on the angle, the steeper the faster. Therefore it is not really fair to compare the flat ramp with the quarter pipe because the quarter pipe will always have its horizontal distance equal to its vertical fall. So the only fair comparison is for the flat ramp to have φ=450. In that case, a=g(1-μ)/√2. I calculate that the speed at the bottom is vflat_ramp=√(2gh(1-μ)).

-

For the quarter pipe, the situation is much harder to calculate because the normal force gets larger as the skater falls thereby increasing the friction. Newton's equations are ΣFx=mgcosθ-μN=ma and ΣFy=N-mgsinθ=mv2/R where a is the tangential acceleration and R is the radius of the pipe. I have no idea how to solve these because they are coupled, second-order, nonlinear differential equations. I am guessing that there is not a closed-form analytical solution and the equations would have to be solved numerically. For this case, though, we are interested in cases where the friction is low, μ<<1. We can calculate the velocity v as a function of θ for the no-friction case, μ=0 and then use that v to approximate the normal force as a function of theta and use that to find the energy lost to friction: v(θ)≈√(2gRsinθ), N≈3mgsinθ, f≈3μmgsinθ. Using these, I find v¼pipe≈√(2gh(1-3μ)).

So, to do a numerical example, R=h=12 ft, μ=0.1, g=32 ft/s2, vflat_ramp=26.3 ft/s, v¼pipe≈23.2 ft/s. (v=27.7 ft/s for zero friction.)

![]() ADDED

COMMENT:

ADDED

COMMENT:

The person who suggested approximating the velocity as the zero-friction

velocity for the ¼ pipe performed numerical solutions for the

differential equations.

His post: "Out of curiosity, I simulated the setup. With μ=0.001 and

m=R=g=1 I got E=0.99701, in agreement with your result.

μ=0.01 leads to

E=0.9704. Even with μ=0.1, the approximation is not bad:

E=0.732.

The mass stops at the center for μ>0.60. Tested with 100, 200 and 500 steps: The critical value is somewhere between 0.603 and 0.605. There is no obvious mathematical constant in that range."

Interpreting, his E is the calculated value of the kinetic energy divided by mgh. For this quantity, my approximation was [½mv2/(mgh)]=(1-3μ). Comparing the computed values with the approximated values: 0.99701≈0.997 for μ=0.001, 0.9704≈0.97 for μ=0.01, and 0.732≈0.7 for μ=0.1. Thanks to mfb for his interest and calculations!

![]() QUESTION:

QUESTION:

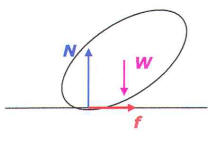

I was told that when a car is moving on a circular banked road. If the car reaches a very high velocity then it may move up the slope of the banked road! Is this possible and if so how?

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

The

figure shows the car on the track. Three forces on it are the weight

W, the normal force N from the road, and the

frictional force f

from the road. Imagine that it is at rest so that all the forces are in

equilibrium: ΣFy=-W+Ncosθ-fsinθ=0

and ΣFx=Nsinθ-fcosθ=0.

The solutions are f=Wsinθ and N=Wcosθ. Now, if the car has some speed v, the car is still in

equilibrium in the y direction, but now has a centripetal acceleration

in the +x-direction of a=v2/R where R is

the radius of the track. So now, ΣFy=-W+Ncosθ-fsinθ=0

and ΣFx=Nsinθ-fcosθ=mv2/R.

Solving these equations, f=m(gsinθ-v2cosθ/R).

Now, notice that if v0=√(gRtanθ), f=0; at

this speed the car can go around the track even if it is perfectly

slippery. For speeds greater than v0, f will be

negative which means it must point down the slope. As the speed

increases beyond v0, the magnitude of the frictional

force will get bigger and bigger down the incline; but, there is a

maximum value which f can be, fmax=μN

where μ is the coefficient of static friction. The

corresponding velocity may be

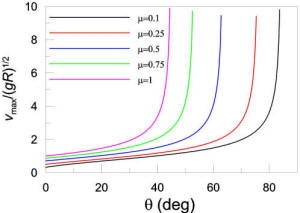

shown to be vmax=‚ąö[gR(sinθ+μcosθ)/(cosθ-μsinθ)].

Not

every angle of incline or every μ will result in the car

slipping, however. Whenever (cosθ-μsinθ)]=0,

vmax=∞ and the car will not slip no matter how

fast it goes. For any given μ there will be a minimum angle θmin=tan-1(1/μ)

beyond which slipping will never occur; for example, for μ=0.5,

θmin=tan-1(2)=63.40.

The graph shows the behavior of vmax as a function

of angle for several values of μ.

Not

every angle of incline or every μ will result in the car

slipping, however. Whenever (cosθ-μsinθ)]=0,

vmax=∞ and the car will not slip no matter how

fast it goes. For any given μ there will be a minimum angle θmin=tan-1(1/μ)

beyond which slipping will never occur; for example, for μ=0.5,

θmin=tan-1(2)=63.40.

The graph shows the behavior of vmax as a function

of angle for several values of μ.

If you want a way to understand this qualitatively and you have worked with fictitious forces in accelerated frames, you can look in the frame of the car and there will be a centrifugal force pointing in the -x direction; this force will have a magnitude of mv2/R and, if it is greater than Nsinθ-fcosθ=N(sinθ-μcosθ) the car will move up the incline.

![]() QUESTION:

QUESTION:

There's an e-skate (electric skateboard) that I'm looking at that says it has 7 Nm of constant torque

and the radius of the wheel is 40 mm=0.04 m. How many seconds would it take to bring me (85 kg) to its top speed of 40 km/h? Their 4WD version says it has double torque, so 14 Nm. How long would that take to get to top speed? The e-skate is Mellow Drive. Other brands have lots of initial torque, but it drops as speed increases. Is this possible to calculate in the same way?

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

The torque on the drive wheels will result in a frictional force between

the wheels and the road which drives the board forward. I am assuming

that that is the net torque to the two wheels, not the torque to each

wheel. So if the torque is 7

Nm, the force accelerating you is F=7/0.04=175 N. Ignoring all

friction, the

resulting acceleration would be a=175/85=2.1

m/s2. If the final velocity is v=40 km/hr=11.1 m/s,

the time is t=v/a=5.4 s. Now, is friction really

negligible? First consider the frictional force f from the

wheels which could be approximated as f=μmg where μ

is a coefficeint kinetic friction and mg=85x9.8=833 N. A

reasonable approximation for μ would be μ≈0.1;

with this μ the unpowered board would stop in about about 20

m if it had a speed of 2 m/s. The frictional force would then be about

83 N, not at all negligible. Redoing the calculations above for a net

force of 175-83=92 N, I find t=10.3 s. Finally we should talk

about air drag. The drag force D may be approximated (only in

SI units) as D≈¼Av2 where

A is the cross-sectional area you present to the wind, let's say

about A≈1 m2; so the biggest D gets

is about 30 N. Since most of the time spent is at lower speeds where

D is much smaller, I will not calculate the the time including

D (a much harder calculation because the force is not constant)

since all this is only a rough caclulation anyway; just think of 10 s as

a lower limit. You can, though, estimate the maximum speed if the torque

really did remain constant by finding the speed for which D=92

N: vmax≈√(4x92/1)≈19 m/s; this is

called the terminal velocity. For

constant torque, doubling it would result in a net force (again

neglecting D but including f) of 267 N and a time of

3.5 s. If you know how the

torque varies with speed, you could do a similar calculation but it

would be trickier because the force and therefore the acceleration would

change with time.

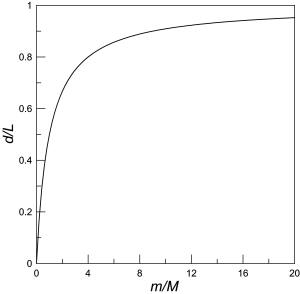

![]() ADDED

COMMENT:

ADDED

COMMENT:

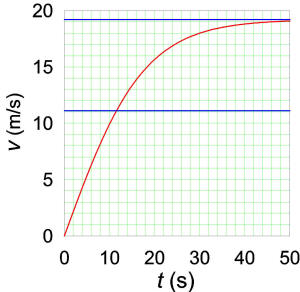

Just for fun I added the air drag D for the two-wheel drive

case. I found that 11.1 m/s is reached in 11.5 s, only a very small

increase as I anticipated. The graph of v vs. t is

shown; you can see that the curve is nearly linear up to 11.1 m/s and

approaches 19.2 m/s at large times. The solutions are t=17.5·tanh-1(v/19.2)

and v=19.2·tanh(t/19.2). Don't take any of this

too seriously because of the numerous approximations I have made; I

would guess there would be about a 30-40% uncertainty—probably

5-15 s would give the experimental time. If you get one of these, let me

know how long it actually takes.

![]() FOLLOWUP QUESTION:

FOLLOWUP QUESTION:

Someone said the mechanical power needed to ride at 40 kmh was 1900 KW. Is that true?

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

The power P delivered by a torque τ at

angular velocity ω is given by P=τω.

In your case τ=7 N·m and ω=v/r=11.1/0.04=278

s-1, so P=1943 W, not kW.

![]() QUESTION:

QUESTION:

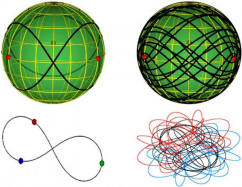

Hello, I'm looking for a physics expert to help me with a problem. We were learning Simple Harmonic Motion in our class today and I was struck with curiosity when my professor showed us a ball rolling without slipping on a turntable. The motion that the ball took surprised me because I never imagined that it would move in that fashion. I then started to wonder if it was possible to describe the ball motion in terms of (x,y) for a function of time. I talked to my professor about this problem and it had him stumped. Can you please help me out with this problem and explain in detail how you got your solution.

Here’s the full question I’m proposing and all the conditions:

A spherical ball of mass ‚Äúm‚ÄĚ, moment of inertia ‚ÄúI‚ÄĚ about any axis through its center, and radius ‚Äúa‚ÄĚ, rolls without slipping and without dissipation on a horizontal turntable (of radius ‚Äúr‚ÄĚ) describe the balls motion in terms of (x,y) for a function of time.

**The turntable is rotating about the vertical z-axis at a constant unspecified angular velocity.

**Radius and mass of the turntable and the ball are unspecified.

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

I was unfamiliar with this problem, but it is interesting. Although the

path of the ball depends on the initial conditions, apparently if you

just set it on the turntable it will

move in a circle

which is at rest in the laboratory frame. I will tell you at the outset

that this is a quite advanced classical mechanics problem and is well

beyond the purposes of this site. However, it was interesting enough to

me that I did a little research to try to get a feeling for how it can

be approached. I will not provide details, but they can be found in a

1979 article in American Journal of

Physics. I do not know your level, but if you are a high school

student, the math is probably beyond your grasp, all the vector

calculus. As you can see from the article, trying to write the solution

in Cartesian coordinates, as you have specified, is not the way to go.

Using the vectors r and ω

as the author does implies using cylindrical polar coordinates (r,

θ, z).

![]() QUESTION:

QUESTION:

Ok so I am in AP Physics 1 and we are learning about Circular Motion. When

I was doing a problem I noticed a problem in which a car is set at a

constant speed and it asks what the free body diagram looks like at the top

of the hill. As I'm doing multiple questions I think about what the free body

diagram would look like just after passing the top of the hill so not at the

top but not fully down the hill. I tried to do the trick where you set it to

an x and y plane but there is no force inwards from the Normal Force and

then of course there's the Weight Force.... If a more skilled Physcisist could

help me it would help so much in furthering my understanding in physics.

![]() COMMENT:

COMMENT:

This student and I had a spirited debate about what constitutes homework

or tutoring help, forbidden on Ask the Physicist. His argument

was "…the

question I brought to your attention does not exsist…" because he

could not find it in a book somewhere and therefore not classifiable as

homework; that, of course, is nonsense because this is a very standard

question. Nevertheless, since he is so avid to learn, I am going to

answer it!

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

The question is kind of ambiguous because it refers to

constant speed; but if the car is to maintain constant speed down the

hill, there will have to be some drag friction. If a constant speed

v is maintained, the free body diagram is shown on the left. I will

choose a coordinate system with +y pointing along the direction

opposite the normal force and +x tangent to the circle and

pointing downhill. The car is inequilibrium in the x direction and has

an acceleration of magnitude v2/R in the

positive y direction. Newton's laws are ΣFx=0=mgsinθ-f

and ΣFy=mv2/R=mgcosθ-N.

The solutions are simply obtained: f=mgsinθ

and N=m[gcosθ-v2/R].

An interesting result is that when θ=cos-1(v2/(gR)),

N=0 and the car will leave the road.

Another possible case is that there is no friction and the car has speed

v

at the top of the hill; the car will therefore speed up as it goes down

the hill. Using energy conservation it is easy to show that its speed

when at angle

θ is v'2=v2+2gR(1-cosθ)

and so the centripetal acceleration is ay=v2/R+2g(1-cosθ).

Notice that there will also be a tangential acceleration, ax,

an unknown at this stage. Now the equations to solve are ΣFx=max=mgsinθ

and ΣFy=m(v2/R+2g(1-cosθ))=mgcosθ-N.

The solutions are ax=gsinθ

and N=m(v2/R+g(2-3cosθ)).

Again, there will be an angle for which N=0 which is where the car would

leave the road, the determination of which I will leave to my AP

student.

![]() QUESTION:

QUESTION:

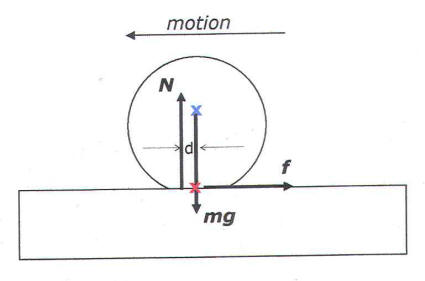

Say you have a conveyor belt with constant speed v. I put a bottle on the belt suddenly.

How do I know that it would not tip and whether there is a critical speed for the conveyor belt so tipping would never happen?

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

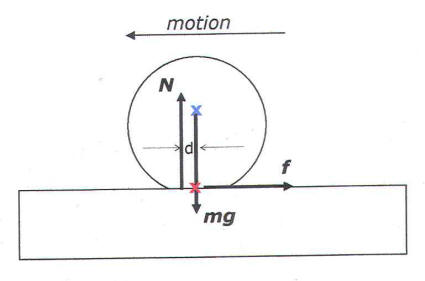

I believe that it depends only on the geometry of the bottle and on the

coefficient of kinetic friction μ between the bottle

and the belt. In the figure, H is the position of the center of

mass ⊗ of the

bottle above the base and R is the radius of the base. When the

bottle touches the belt there will be a frictional force f

in the same direction as the velocity of the belt which will cause an

acceleration of the bottle to bring it up to the belt speed. But, as you

note, the bottle might tip over because of the torques it experiences

due to the forces on it. Because the bottle is trying to tip, the normal

force on the bottle should be expressed as two different forces

N1 and N2

acting on the leading and trailing edges of the base. Since the bottle

is accelerating, it is imperative to calculate the torques about the

center of mass of the bottle. The bottle is in equilibrium in the

vertical direction so N1+N2=mg.

The frictional force is f=μ(N1+N2)=μmg.

The torques will sum to zero if the bottle is not tipping, 0=fH+RN1-RN2.

Now, if the bottle is just about to tip over, N1=0

and so the torque equation becomes 0=fH-RN2=μmgH-Rmg

or μmax=R/H; this is the

maximum that the coefficient of friction could without the bottle

tipping. The result does not depend on either m or v.

For example, if R=3 cm and H=6 cm, then μ≤0.5.

![]() ADDED

NOTE:

ADDED

NOTE:

The normal force could have been handled differently by having a single

force N acting a distance d from the leading edge of the base of the

bottle. Then when d=2R the bottle would be about to

tip. You would get the same result as above.

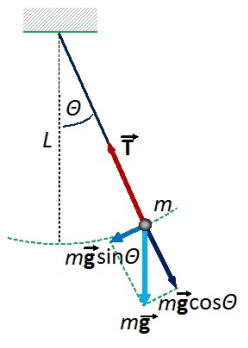

![]() QUESTION:

QUESTION:

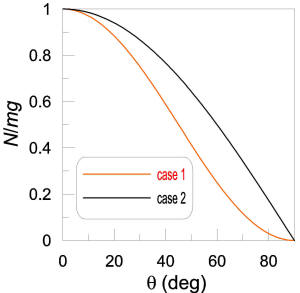

I am standing on a scale on carriage that is going down the slope without friction. The slope angle is

theta. What will the scale show in two cases:

-

The carriage is shaped in a way that the scale is horizontal with respect to ground (that is is a special edge shaped carriage)

-

The carriage is regular so the the scale is not paralleled to the ground.

I am trying to understand how a special wedge or insoles in ski show would effect weight felt by a person. In case 1 I think the answer should be mg(1-(sin(theta)^2)) but I am not sure.

In case 2. I have no idea. I think scales can misfunction if the slope is too strong.

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

Before doing either case, imagine that we choose the man and the

carriage as the body to look at. It is the standard introductory physics

problem of something sliding down a frictionless incline. The principle

result is that the acceleration of the man and the carriage are the same

and have a magnitude a=gsinθ down the

slope.

-

The figure on the left shows the forces on the man standing on the horizontal scale. There is his own weight, mg and the scale exerts a normal force N vertically up; the scale will read N. The contact between the man and the scale cannot be frictionless or else the man would not accelerate along with the carriage, so there is also a frictional force f. Newton's equations for the man are ma=mgsinθ=-Nsinθ+fcosθ+mgsinθ and 0=Ncosθ-fsinθ-mgsinθ. Solving, I find N=mgcos2θ and f=mgsinθcosθ.

-

The figure on the right shows the man on the scale parallel to the incline. Now no friction is needed and the scale, again, will read N but N will be different. Newton's equations are 0=-mgcosθ+N and ma=mgsinθ, just the same as the classic object on the frictionless incline. So the scale reads N=mgcosθ.

The graph compares the two cases.

![]() QUESTION:

QUESTION:

If two people are carrying a canoe parallel to the ground, how much weight are they each carrying? would it be half of the weight of the canoe, more than half, or less than half?

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

It all depends on two things—where the center of gravity is

and where the two people exert their forces. In the figure the weight

W of the canoe acts at the center of gravity

and the two people exert forces F1

and F2 at distances at distances

d1 and d2 from the center of

gravity. The two people must hold up all the weight between them, so

F1+F2=W. The canoe is not

rotating about its center of gravity so the net torque must be zero, so

F1d1=F2d2.

Solving, F1=W[d2/(d1+d2)]

and F2=W[d1/(d1+d2)].

If d1=d2, each holds up half the

weight.

![]() QUESTION:

QUESTION:

I'm shopping for a pole chainsaw and trying to figure how heavy a 7 lbs saw at the end of a 8' pole would "feel", at about a 45 degree angle.

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

It depends on how you hold it and where the center of gravity is. Refer

to the figure. The weight W acts at the center

of gravity which I have chosen to be at a diatance c from your

right hand. The position of your left hand I have denoted as being a

distance d from your right hand. For simplicity I have assumed

that you will exert a force L with your left

hand perpendicular to the pole; your right hand exerts a force with

horizontal and vertical components H and

V respectively. You specify 45°, so

the horizontal and vertical components of L

are equal and of magnitude L/√2. The two equations for

translational equilibrium are ΣFvertical=0=-W+L/√2+V

and ΣFhorizontal=0=-L/√2+H.

These may be simplified to H=L/√2 and V=W-H.

There are three unknowns and only two equations, so we need a third

equation; the sum of torques must also be zero. Summing torques about

the right hand, Στ=dL-cW/√2=0 or L=cW/(d√2).

Therefore, H=cW/(2d) and V=W[1-cW/(2d)].

For example, suppose W=7 lb, d=3 ft, c=4 ft:

I find L=6.6 lb, H=4.7 lb, V=2.3 lb. The

force R exerted by your right hand is R=√(V2+H2)=5.2

lb. The key to easy handling is to choose the saw with the smallest

c which will minimize the torque you must exert.

![]() QUESTION:

QUESTION:

How does a torque applied to a wheel cause translational motion? Please don't say the ground pushes on the wheel.

The wheel is stationary at the road surface. From my understanding friction creates a torque equal to the driving torque so where does the net accelerating force come from and where does it act? If you could explain with a free body diagram showing all the forces present that would greatly enhance my understanding.

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

If you are asking someone to explain something you do not understand,

don't tell them what not to say! You have, in essence, asked me to not

answer your question because it is the friction which accelerates your

car forward. Let me see if I can explain it to you. Suppose you have a

car with its brakes on at rest on a road. You get behind the car and

push as hard as you can but, alas, it will not budge. What force is

preventing it from moving? The road exerts a static frictional force on

the car, even though it is "stationary"; then, clearly, you cannot say

that the road cannot push a surface in contact with it just because the

surfaces are not sliding on each other. Suppose that there were no

friction between the tire and the road and the car was at rest. No

matter how hard you push your engine which, through the transmission and

various linkages, exerts a torque on the wheels, you would go nowhere,

the torque just spinning the wheels. But, if there is friction, the

wheel, at the point of contact with the road, would exert a force on the

road (opposite the direction you want to go). But Newton's third law

tells you that if the wheel exerts a force on the road, the road exerts

an equal and opposite (forward) force on the wheel. That is the force

which accelerates that car forward.

![]() QUESTION:

QUESTION:

A steel pole weighing 1000kgs and is 9 metres long what would the weight of the pole be on the end if I tried to lift it from the end?

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

First, let's get one thing clear—the weight of something is the

force which the earth exerts on it and never changes. Also, technically

a kilogram is a unit of mass but I will treat it as a weight since many

countries do. What you want, I believe, is the force you need to exert

to lift it.

It is not really clear what it means to lift "from the end". Two

scenarios suggest themselves to me:

-

Lift it from one end while the other end rests on the ground

In order for the rod to be just barely lifted off the floor at one end, the torque due to F must be equal in magnitude to the torque due to W=1000, 9xF=4.5x1000=4500 or F=500 kg. The floor holds up the other half of the weight.

-

Grab onto one end and lift the whole rod keeping it horizontal.

It is impossible to lift it horizontally using only a force at the end because you could not exert enough torque to keep the rod from rotating due to the torque caused by the weight. You might try to do it by using two hands, one at the end pushing down and the other some distance d from the end pushing up. In that case (see the figure above), summing the torques about the end you find that Fup=4500/d; for example, choosing d=20 cm=0.2 m, Fup=22,500 kg. You can also find Fdown by summing all forces to zero, Fup-W-Fdown=0=22,500-1000-Fdown or Fdown=21,500 kg.

![]() QUESTION:

QUESTION:

According to third law of motion a bird sitting on a tree branch cannot fly due to reaction then how does it fly?

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

Why would you think that? The so-called reaction force is exerted down

on the branch, not on the bird. Let's dissect the physics of this bird.

The eagle on the left is sitting on a branch. There are two forces on

him—his weight W and the force

the branch exerts up on him F. These forces

are equal and opposite because of Newton's first law. But, what

about the reaction partner of F, the equal and

opposite Newton's third law partner? That force is the force which the

eagle exerts down on the branch and is not a force on the eagle

(which is why I did not even draw it in the force diagram of the eagle).

The picture on the right shows the eagle just as he is lifitng off. Now

there is an additional force L due to the lift

generated by the flapping wings. Since L+F>W, the eagle is no

longer in equilibrium and will accelerate upward. As soon as the talons

leave the branch, F disappears.

![]() QUESTION:

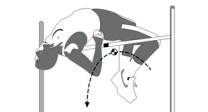

QUESTION:

This past weekend I was in Vermont and was walking down a relatively steep gravelly road when I started gaining speed unintentionally and it seemed as thought my feet couldn't keep pace with the top half of my body. I kept accelerating for about 20-25 paces and saw a tree looming in front of me when I fell down flat.

Is there a name for what happened and is there

anyway I could have stopped it once it began? I ask because this happened to me once before in almost the same conditions years ago and, at the time, I ended up with 2 missing front teeth, a black eye, and bruises/cuts on both forearms.

anyway I could have stopped it once it began? I ask because this happened to me once before in almost the same conditions years ago and, at the time, I ended up with 2 missing front teeth, a black eye, and bruises/cuts on both forearms.

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

I have had this happen to me and know the helpless feeling of not being

able to stop running. The red arrow in the picture represents your

weight, acting at your center of gravity somewhere in your trunk. This

force exerts a torque about your leading foot which tends to rotate you

in a clockwise direction. Imagine that this runner were not running but

just standing still. The only way to keep from falling forward (rotating

about that leading food) would be to exert an opposite torque and this

could only be done by your foot/ankle; but the requisite muscles are not

strong enough to exert the necessary torque. Think about it—if

you were just standing on level ground, how far could you lean forward

without falling forward? Not very far! And it is even worse if you are

running because you have a forward momentum which also is tending to

topple you forward if you try to stop. All that I can think of that you

can do to avoid a fall is to try to slow enough that you can get

yourself more vertical so that your center of gravity is vertically

above your feet. If the hill is not too long, you can keep running until

you get to the bottom, but you will be speeding up the whole way.

![]() QUESTION:

QUESTION:

How many g forces will a driver experience accelerating from 0 to 200 mph

in 1/4 mile, straight line acceleration.

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

No homework. But there are lots of advertisers on this page which will help

with homework.

![]() FOLLOWUP:

FOLLOWUP:

This is not homework.

It happens to come from one of the

country's top 100 trial lawyers who would have gone to medical school

instead if he had the math ability to figure this out myself.

Of course, I have lost two trials in 28 years and my time goes for $650 an h)p8

I will just have an associate do it for me tomorrow--if it is still of any concern.

This is the first time that I have ever used one of these "Ask Jeeves" sites and will be the last.

And my new Vette has a g force display so if I really wanted to know I would have gotten in and fkoored it instead of relying on some bottom feeder like you.

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

Wow! I am so excited to get a question from one of the country's top 100

trial lawyers. I am so honored, even though I am just a tiny "bottom

feeder" in the presence of such a paragon. Sorry for the sarcasm, dear

readers, but this is a good opportunity for me to emphasize that one of

the important things about Ask The Physicist is that it is not a

homework help or tutoring site. I feel very strongly about this because,

having been a teacher for 40 years, I feel strongly that students should

do their own work and the internet gives too many opportunities for

"cheating" in that regard. I reject what I judge to be homework

questions and, inevitably, I occasionally make a mistake. If you think

my ethical stand on this issue makes me the scum of the earth, so be it.

When I do make a mistake, I usually answer the question and I will do

that here. The equations of motion for uniform acceleration for the

object starting at rest are v=at and d=½at2

where, in this case, v=200 mph=89.4 m/s and d=¼

mile=402 m. The time can be eliminated using the first equation, t=89.4/a

and substituting into the second equation, 402=½a(89.4/a)2=3996/a

or a=9.94 m/s2. The acceleration due to gravity

is 9.8 m/s2 and so this is just about 1 g of acceleration,

a=1.01g. I figure that anyone who charges $650/hour

for his services can afford to send a little of that my way!

![]() QUESTION:

QUESTION:

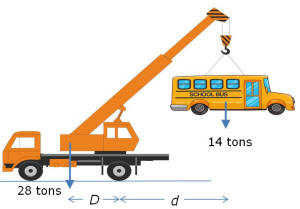

From the physics theories and calculation, how does a crane fall of a bridge when trying to pull out a bus from the water? (crane = 28 ton, bus = 14 ton)

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

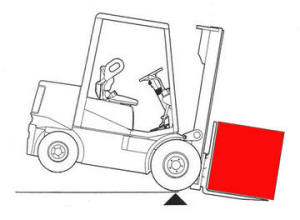

It's all about the torques. In the figure, if the crane tips over it

will rotate about the rear wheel. When this is just about to happen the

front wheel has zero normal force from the road on it. At this time, the

road exerts a 42 ton force up on the rear wheels (they are holding up

all the weight). The weights each act at the center of gravity of the

crane and the bus. If I sum torques about the rear wheel, they must

equal zero, that is 28D=14d or d/D=2.

So, if d is greater than 2D, the whole system will

rotate about the rear wheels and topple off the bridge.

![]() QUESTION:

QUESTION:

If you had two point masses m1 and m2 in space separated by a distance d, how long would it take for them to collide under gravity alone? I'd imagine it's a changing force/acceleration, so some calculus must be involved.

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

I have solved this problem many times before but always for specific

masses and distances. To avoid the calculus you refer to, the trick is

to use Kepler's laws for planetary motion. You can find references on the

FAQ page. The one you

might find most useful is this

link. You will see that

the relevant time to collision is t=T/2=√(πμa3/K)

where μ=m1m2/(m1+m2)

is the reduced mass, a=d/2, and K=Gm1m2.

Therefore, t=√[πd3/(8G(m1+m2)].

![]() QUESTION:

QUESTION:

A tire rolling on a level surface at a linear speed of 10 MPH rolls on to a conveyor belt which is also moving at 10 MPH in the same direction. How will the tire's speed change? Will it be 20 Mph? 10 MPH? Will it's rotation stop?

Reverse?

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

This problem is a little trickier than I had anticipated. On the other

hand, the final answer is much simpler than I had anticipated. Shown in

the figure to the left is (top) the situation when the rolling tire

first touches the conveyer belt. It is rolling without sliding so the

point of contact with the floor is at rest, the center is moving forward

with a speed v (your 10 mph), and the top is moving forward

with speed 2v; the belt is moving forward also with speed v.

I find this problem much easier to do if I transform into a coordinate

system which is moving with speed v to the right; in that

coordinate system the belt (upper surface) and tire are both at rest and

the top and bottom edges of the tire have speeds v as shown.

Before getting into the hard part, there is a special case which we can

get out of the way first: if there is no friction the tire will continue

on its merry way unchanged, both its speed and its angular velocity

unchanged because there are no net forces or torques on it.

Now,

as soon as it gets on the belt there will be a frictional force

f trying to accelerate it to the right so it will

start sliding along the belt (at rest in the frame we are using). The

frictional force will be f=μmg where μ is the

coefficient of kinetic friction, m is the mass of the tire, and

g is the acceleration due to gravity. Call v' the

speed which the center acquires in some time t. Then Newton's

second law for translational motion is mΔv=μmgt=mv',

so v'=μgt.

There

will also be a torque τ=fr=μmgr which acts opposite the

direction the tire is rotating. There will come a time when the bottom

edge of the tire will be at rest relative to the belt because of this

torque. At that instant, we can transform back into the original

coordinate system and the tire will be moving forward with speed

v+v'. Newton's second law for rotational motion is ΔL=τt=-(μmgr)(v'/μg)=-mv'r.

where L is the angular momentum of the system. The angular

momentum is the angular momentum about the center of mass plus the

angular momentum of the center of mass. L1=Iω1+0=Iv/r

where I is the moment of inertia about the center of mass;

L2=Iω2+mrv'=(v'/r)(I+mr2).

Therefore, (v'/r)(I+mr2)-Iv/r=-mv'r

or, v'=Iv/(I+2mr2). This is

surprisingly simple, particularly surprising that it does not depend on

μ. However, the time to stop sliding does depend on μ,

t=v'/μg; the slipperier the surface, the longer it

takes to stop slipping, as expected.

Finally

we need to transform back into the original coordinate system by simply

adding v as shown in the final figure. As an example, suppose

we model the tire as a uniform cylinder of mass m and moment of

inertial I=½mr2; then v'=v/5,

or in your case, 2 mph, so the tire is rolling without slipping with a

speed of 12 mph.

![]() ADDED

NOTE:

ADDED

NOTE:

Note that the new angular velocity of the tire is ω'=v'/r

only a small fraction of the original value of ω=v/r.

This drop in angular velocity can be clearly seen in a

Mythbusters

episode showing a car driving onto a ramp from a moving truck, a

very similar situation to the conveyor belt problem in this question.

![]() QUESTION:

QUESTION:

I was wondering if, when an object enters earth's atmosphere from space, does it experience a lateral force as it enters the atmosphere? In other words, does it suddenly get "pushed" sideways due the earth's rotation?

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

This had never occurred to me, but certainly the meteorite will be

deflected because of the "wind" of the rotating atmosphere. But, how big

an effect is this? The average speed of a meteorite is about 17 km/s;

and I calculate the speed of the "wind" to be about 0.47 km/s at the

equator. So, even if the meteorite acquired all of the speed of the

atmosphere, it will still be trivially small compared to the vertical

speed. Another way to look at it is to look at the drag forces the

meteorite experiences when it encounters the atmosphere; these are proportional

to the squares of the speeds, so the ratio of the horizontal force to the

vertical force will be about 0.472/172=0.0008. Compared to the force slowing down the vertical motion, the force

speeding up the horizontal motion is tiny.

![]() QUESTION:

QUESTION:

I have a question related to determining the force at impact.

Here's the question in two parts:

-

If a firefighter adds 45 pounds of gear to his overall weight, does it increase the impact force if he has no choice but to jump out a window and if so to what degree?

-

What is the effect on impact force of jumping out a second floor window vs. 3rd floor and above?

This actually isn't homework. I'm 54 years old and advising a charitable organization that provides safety systems to firefighters. One of the challenges they face is fire departments who don't have high rise buildings and feel they don't need the bailout systems. So I'm trying to figure out what the impact is for a firefighter forced to jump out a second story or third story window. This will help inform how they talk to prospective donors. If you could help me with that (understanding/identifying the increase in impact force from 1st to 2nd to 3rd floors and then up) it would be greatly appreciated. I've done a lot of googling around calculating impact and g forces, but its not making sense to me (I'm not being lazy, just not understanding).

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

The "force at impact" depends, essentially, on the time to stop. If she

has a speed v, a mass m, and stops in a time t,

the average force F during the stopping time is given by

F=m(g+v/t) where g=32 ft/s2 is the acceleration due to

gravity. So, yes, if you increase the mass you increase the force

proportionally; I guess I would toss that extra 45 lb over before I

jumped! Regarding your second question, call the height of one floor

h. Jumping from the second floor would result in a speed of v2=√(2gh);

jumping from the third floor would result in a

speed of v3=2√(gh) which is

about 1.4 times larger than v2. In general, jumping

from the nth floor would result in a speed vn=√[2(n-1)gh].

Maybe some numerical examples would be useful to you. You prefer Imperial units, which makes things a little complicated. The quantity mg is the weight. I will take mg=160 lb and h=12 ft for my numerical calculations, so when I need the mass I will use 160 lb/32 ft/s2=5 lb·s2/ft. (The unit of mass in Imperial units is called the slug, 1 slug=1 lb·s2/ft.) The speeds from second and third floors will then be v2=27.7 ft/s=18.9 mph and v3=39.2 ft/s=26.7 mph; these speeds are independent of the mass. Finally we must approximate the times to stop. If she lands feet first, she could extend, as parachutists do, her stopping time by bending her knees into a squat; I will estimate the distance s she will travel while stopping as s=3 ft. The time may be shown to be t=2s/v so t2=2x3/27.7=0.22 s and t3=2x3/39.2=0.15 s. Finally, the average forces during impact are F2=160+5x27.7/0.22=790 lb and F3=160+5x39.2/0.15=1467 lb. These are approximately 5 and 9 times her weight (g-forces of about 5g and 9g).

![]() QUESTION:

QUESTION:

Well

I hope this doesn't seem off the wall but I want to know how much force

it would take to tip a 7.62 m tall,6.40 m wide and 22 ton Transformer over? It is for a story I'm doing about a comic book character.

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

It depends on where and how the force F is

applied; if applied as shown in the diagram, it will be the smallest

possible.

I will assume that the center of gravity of the transformer is in the

geometrical center, so the weight W acts

there. When the force is just about to tip it over, all the force from

the floor, the normal force N and the

frictional force f, act on the edge opposite

where the force is applied. It will be in equilibrium, so you can easily

see that F=f and N=W. But, what you need is F

and to get it you need to sum the torques around the edge where N

and f act and sum to zero: Fh-Ww/2=0 or F=Ww/(2h).

Using your numbers, F=22x6.40/(2x7.62)=9.24 tons. If you want

the force in Newtons, assuming that the 22 ton mass is metric tons

(22,000 kg), F=9.8x9240=90,500 N.

![]() QUESTION:

QUESTION:

If you tow a boat from a tow path which is the best point to tie the rope onto the boat?

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

The rope will exert a force on the boat, obviously. This force will tend

to do three things: exert a torque which will tend to rotate the boat

about a vertical axis through the center of gravity (you don't want

this), have a component along the bank which will pull it along the

canal (that is what you want), and have a component which will pull the

boat toward the shore (you don't want this). To minimize the tendency of

the boat to turn, attach the rope close to the center of gravity of the

boat. To minimize the tendency to drift (not turn) to the bank, make the

rope as long as possible so that most of its force will be exerted along

the bank. Some tiller will be needed to make small corrections, but

those should be minimal.![]() QUESTION:

QUESTION:

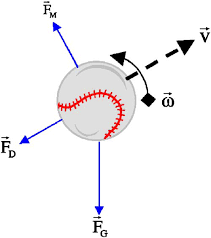

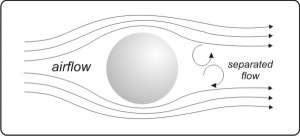

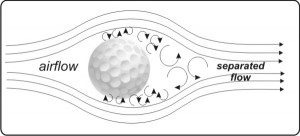

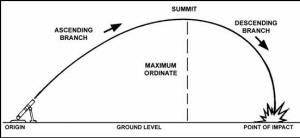

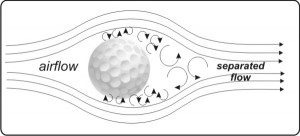

I am an avid sports fan and I have often wondered if the experts may be wrong about the myth of the rising fastball in the game of baseball. I played baseball for over 20 years and I can tell you that the ball does appear to rise when certain pitchers throw hard put a heavy backspin on the ball. I have been told that experts say it is nothing more than a visual trick your eyes play on you because a rising fastball is considered to be physically impossible. I can tell you first hand that a softball pitcher I know can throw a ball that rises after being thrown on a straight trajectory. I suspect the Magnus effect may have something to do with the anit-gravitational behavior of the ball. Do you think this could be what causes the ball to appear to rise as it travels, or is it just our perception?

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

There is such a thing as a rising fastball, but it does not actually

rise; it simply falls more slowly than a nonspinning ball does. An

experienced hitter knows intuitively what a normal fastball does and

when presented with a rising fastball he will swear that it rose because

it actually fell less. Incidentally, by rise or fall, I am talking about

the direction of the acceleration. So a ball which is thrown at an angle

above the horizontal is obviously rising but it rises at a

decreasing

rate of rise until it reaches the peak of its trajectory and then begins

back down; the rising fastball will actually rise farther. Then why do

we say it is a myth? It is easiest to understand by looking at a ball

thrown purely horizontally. Can spin cause the ball to actually go

upwards? To answer this, you need to think about all the forces on a

pitched ball. There is the weight, FG, which points

vertically down and causes the ball to accelerate downward (a

horizontally thrown 90 mph fastball falls about 4 feet on the way to the

plate); there is the drag FD which points opposite

the direction of flight and tends to slow the ball down (a

90 mph fastball

loses about 10 mph on the way to the plate); and there is the magnus

force FM which, for a ball with backspin ω

about a horizontal axis points perpendicular to the velocity and upward.

If the ball is moving horizontally the only way it could rise is for the

Magnus force to be larger than the weight. Measurements have been done

in wind tunnels and it is found that if the rotation is 1800 rpm, about

the most a pitcher could possibly put on it, the ball would have to be

going over 130 mph for the Magnus force to be equal to the weight. When

you say "thrown on a straight trajectory", you cannot mean it left his

hand horizontally because it would hit the ground before it got to the

plate; a fast pitch like that is impossible to accurately judge the

initial angle of the trajectory.

decreasing

rate of rise until it reaches the peak of its trajectory and then begins

back down; the rising fastball will actually rise farther. Then why do

we say it is a myth? It is easiest to understand by looking at a ball

thrown purely horizontally. Can spin cause the ball to actually go

upwards? To answer this, you need to think about all the forces on a

pitched ball. There is the weight, FG, which points

vertically down and causes the ball to accelerate downward (a

horizontally thrown 90 mph fastball falls about 4 feet on the way to the

plate); there is the drag FD which points opposite

the direction of flight and tends to slow the ball down (a

90 mph fastball

loses about 10 mph on the way to the plate); and there is the magnus

force FM which, for a ball with backspin ω

about a horizontal axis points perpendicular to the velocity and upward.

If the ball is moving horizontally the only way it could rise is for the

Magnus force to be larger than the weight. Measurements have been done

in wind tunnels and it is found that if the rotation is 1800 rpm, about

the most a pitcher could possibly put on it, the ball would have to be

going over 130 mph for the Magnus force to be equal to the weight. When

you say "thrown on a straight trajectory", you cannot mean it left his

hand horizontally because it would hit the ground before it got to the

plate; a fast pitch like that is impossible to accurately judge the

initial angle of the trajectory.

![]() QUESTION:

QUESTION:

In lifting an object to a higher level directly over its original location, the energy I expend increases potential energy. But, does some of the energy used in lifting it also go to accelerating it to higher rotational velocities as the circumference of its "orbit" increases as it is raised over its original position? Does this add kinetic energy and mass to the object whereas increasing potential energy does not?

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

(Preface: all my calculations below assume that the height lifted is

much smaller than the radius of the earth. I also neglect the change in

the gravitational force over the distance the mass is lifted. Also, to

simplify things, all my calculations are at the equator.) Yes, work is

done to increase the kinetic energy. As viewed from an inertial frame,

watching the mass M get lifted to h, I estimate that

the kinetic energy changes by ΔK≈2hKinitial/R=MhRω2

where R=6.4x106 m is the radius of the earth and ω=7.3x10-5

s-1 is the angular velocity of the earth. For example,

lifting 1 kg a height of 1 m requires 0.03 J of work to increase the

kinetic energy. But wait a minute! Once we acknowledge that the earth is

rotating, we have to recognize that the mass, being in a circular orbit,

has a centripetal acceleration ac=Rω2

and therefore the net force on M is Mg-MRω2.

Therefore, the net work done is W≈(Mg-MRω2)h+MhRω2=Mgh.

![]() QUESTION:

QUESTION:

If I weigh 200lbs and am riding a kick scooter that weighs 14lbs, and I am riding at a speed of 10 mph and I jump the scooter off a curb, say 6 inches, what is the force in terms of pounds, that I am applying to the scooter as it lands?

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

Usually it is not possible to answer this kind of question because what

is needed is to know how long the collision between you and the ground

lasted. In this case, though, we can estimate the time of this

collision. As you may know, paratroupers are trained to not land with

stiff legs, rather to bend at the knees during the landing; the purpose

is to prolong the landing time and this reduces the average force on the

legs during the landing. If a mass M hits the ground with some

speed V and stops in time t, the average force over

the time is F=W+MV/t where W is the weight,

200 lb; to convert the

weight to mass, divide by the acceleration due to gravity, g=32

ft/s2: M=W/g=(200 lb)/(32 ft/s2)=6.25

ft·lb/s2. The speed at impact can be determined

from V=√(2gh)=√[2x(32

ft/s2)x(½ ft)]=5.7 ft/s. If we approximate that

the distance S over which your legs bend on landing as S=1

ft, the time to stop is t=2S/V=(2x1 ft)/(5.7

ft/s)=0.35 s. So, finally, F=200 lb+(6.25

ft·lb/s2)(5.7 ft/s)/(0.35 s)=302 lb. This is

the force the scooter exerts on you which, by Newton's third law, is

equal the the force you exert on the scooter (but in opposite

direction). If you stop in ½ ft, the force would be 404 lb. Keep

in mind that this is a very approximate estimate of the average force.

![]() QUESTION:

QUESTION:

I am having a debate with my brother about climbing on an incline.

I understand the basics of climbing a hill on a diagonal. If you climb diagonally, you can avoid taking larger vertical steps at the cost of more horizontal movement. This makes each step take less energy while increasing the overall work and time needed.

However, it seems as though this rule does not work for stairs. Stairs do not allow for shorter vertical steps (you either make 100% progress on a step or 0%). Do I have this correct? Am I missing something?

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

Slaloming up the incline will increase time spent but not increase work

done. This assumes no frictional forces are important, the only work you

do is the work lifting you. Since work done does not change but elapsed

time does, the average power you are generating going straight up is

greater than zigzaging. Going up steps, though, if you go across a step

you do no work, the only work done is lifting you to the next step. The

only way to get the equivalent lowered average power output as you do by

slaloming up the slope is to rest between steps.

![]() QUESTION:

QUESTION:

How strong would a man have to be to push a 16,000 lb bus on a flat surface?

![]() ANSWER:

ANSWER:

That depends on how much friction there is. And not just the friction on

the bus, but more importantly, the friction between the man's feet and

the ground. Newton's third law says that the force the man exerts on the

bus is equal and opposite the force which the bus exerts on the man (B

in the picture). Other forces on the man are his weight (W),

the friction the the road exerts on his feet (N),

and the force that the road exerts up on him (N).

If the bus is not moving, N=W and f=B, equilibrium.

The biggest that the frictional force can be without the man's feet slipping is

f=μN where μ is the coefficient of

static friction between shoe soles and road surface. A typical value of

μ for rubber on asphald, for example,

μ≈1, so the biggest f could be is

approximately his weight W;

this means that the largest force he could exert on the bus without

slipping would be

about equal to his weight. Taking W≈200 lb, if the

frictional force on the bus is taken to be zero, the bus would

accelerate forward with an acceleration of a=Bg/16000=200x32/16000=0.4

ft/s2 where g=32 ft/s2 is the

acceleration due to gravity; this means that after 10 s the bus would be

moving forward with a speed 4 ft/s. If there were a 100 lb frictional

force acting on the bus, the acceleration would only be a=0.2 ft/s2.

If there were a frictional force greater than 200 lb acting on the bus,

the man could not move it.

![]() QUESTION:

QUESTION:

I'm confused? One moment I'm reading about "inertial reference frames" and that "acceleration due to gravity" is unaffected by mass. This is followed up with examples such as the Bowling ball and feather. All good. Maths seems clear enough.