QUESTION:

QUESTION:

People are worried that Earth is slowly

loosing its moon, because Earth will go

crazy. Mercury and Venus don't have moons

and their orbits and rotations are stable.

What gives?

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

Funny, I have never met a single person

who is "…worried that Earth is slowly

loosing [sic] its moon…". Do you

know the rate at which this is happening?

1.5 inches per year! So tell all those

worried people to stop worrying. There will

be no noticable change for hundreds of

generations. Why do you think "…Earth will

go crazy"? And what does that mean, anyway?

If you are interested in why the moon is

receding rather than coming closer, see an

earlier answer. There is also a

nice video which explains that the moon

will never actually leave the earth.

QUESTION:

QUESTION:

My assumtion: Things that get too hot

eventually glow. Question: Does coolder

matter have some way of binding photons? If

so, What force weakeneds within matter that

it's grip on those escaping photons when the

matter heats up the the point of glowing and

emiting light? I do get that light is always

shinning through different spectra, is it

just the rapidly vibrating hotter matter

that speeds up the wave form of an emited

photon?

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

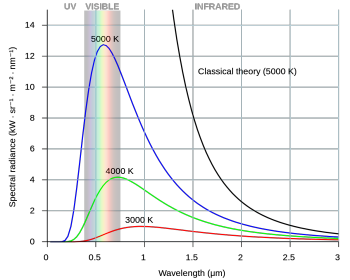

Everything radiates regardless of its

temperature. Most objects are pretty well

described as

black bodies. Also see a

earlier answer of mine. The intensity of

the radiation as a function of the

wavelength of the radiation is shown in the

figure for three temperatures. At 5000 K,

approximately the temperature of the surface

of the sun, the most ratiation is in our

visible range; this is a wonderful example

of evolution, showing that we evolved such

that our eyes are most sensitive to the

wavelengths which illuminate our world. As

the temperature gets cooler, the peak shifts

toward longer (redder) wavelengths; At 3000

K, roughly room temperature, nearly all the

radiation is in the infrared part of the

spectrum where our eyes cannot detect it but

infrared cameras and glasses can. You are

right that as you increase temperature the

radiation in the visible region will become

intense enough to see it. But your idea that

all those emitted photons have been sitting

around waiting to be radiated is totally

wrong. Photons are created when electric

charges are accelerated. The electrons in

the atoms are vibrating about and get

created at the time of emission.

QUESTION:

QUESTION:

What does it mean when 'if a charge is

taken through a potential difference'?

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

It means that the charge moves in a

volume where there is an electric field. It

means that work is done (positive or

negative) on the charge as it moves from one

point to another; the work done is

independent of the path between the two

points.

QUESTION:

QUESTION:

How is it that half the surface of a

sphere [the Moon] can be illuminated with

the same intensity of sunlight rather than a

gradient?

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

I don't understand the question.

REPLY:

REPLY:

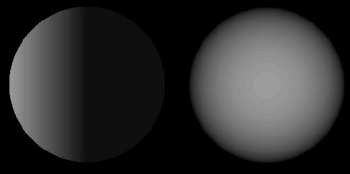

A computer-generated lambertian model

illuminated with collimated light (as from

the sun) contrasted with the illumination of

the moon:

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

It turns out that the reason is quite

simple: The moon is not well-described as

Lambertian surface for numerous reasons. A

good explanation can be seen at this

link.

QUESTION:

QUESTION:

We now know that protons and neutrons

are comprised of 3 quarks. Is there any

reason to believe that is it? Quarks are the

most basic so called 'building blocks' of

particles or...., is it possible quarks are

comprised of some other as of yet

undiscovered particles and so on and so

on...?

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

It is generally believed that, like

electrons, quarks are indivisible particles;

no self-respecting scientist would insist

that it is not possible that they have some

underlying structure. But, the notion that

protons are comprised simply of 3 quarks is

a big simplification. See an earlier

answer for a discussion of this.

QUESTION:

QUESTION:

Hi, as I was surfing the internet I

became interested in the concept of

renormalization and found something related

to it's history quite interesting.

Renormalization is usually credited to three

men, Richard Feymann (the famous one),

Julian Schwinger and Shin'ichirō Tomonaga,

they even received the Nobel, Tomonaga seems

to have published his first paper about

renormalization in 1943, in japanese

(https://academic.oup.com/ptp/article/1/2/27/1877120?login=false).

Is there some reason he is not given a

pioneering role in places like wikipedia and

physics books? I thought the discovery was

made almost simultaneous, but he just was

obstructed by war and language barrier. As

I'm not expert in the subject at hand, does

the first Tomonaga paper lacks something

that makes it not a renormalization paper?

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

I do not understand what is bothering

you so much. All received three were awarded

the Nobel Prize in Physics 1965 for their

contributions to quantum electrodynamics;

you can't get any better recognition than

that. The Wikepedia article on

renormalization credits all three along with

Kramer, Bethe, and Dyson for making

important contributions to renormalization

theory (Tomonaga has the most references).

QUESTION:

QUESTION:

Hopefull I’m not breaking ground rules.

Related to climat change which I beleive is

real.. but the recent finding of a hiker

lost on a gkazier 4 decades ago seems to say

the glazier is at the same point it was at

40 years ago…. So assuming glazier are not

normall ever growing and they seem to ebb

snd flow(is this right). Then this

particular glazier seems to be at the same

point it was at 40 years ago… how does this

knowledge fit in to the obvious climate

changes we seem to be experiencing?

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

I do not see how you can glean any

information from his being found. First,

since he was lost and never found, we have

no idea where he was when he died. Second,

there is a reason why glaciers are called

"rivers of ice"—they are always moving. So

you neither know where this hiker died nor

where that location has moved to over the

intervening time.

QUESTION:

QUESTION:

Distance between 2 planets (A & B) is 10

light years. One spaceship (1) leaves planet

A and travels to planet B at an average

velocity of 0.25c. A second spaceship (2)

leaves planet A 20 years later and travels

to planet B at an average velocity of 0.5c.

Do they arrive at planet B at the same time?

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

It depends on whose clocks you used.

Let's first use clocks on planet A: It

obviously takes a time T1=40

years for #1 and T2=20

years for #2, so, as observed by A, they

arrive simultaneously. Now, #1 would

measure, because of length contraction, the

distance between A and B to be L'1=L1√(1-0.252)=9.68

ly; similarly, #2 would measure that

distance to be L'2=L2√(1-0.52)=8.7

ly. The corresponding times (T=L/v)

would be T'1=38.7 yr and

T'2=17.3 yr. Now we need

to find the speed of #2 relative to #1; [v21=0.5c+0.125c]/[1+(0.5x0.25]=0.286c.

We can now calculate how long it takes

for #2 to catch up with #1, (L2/2)/v21=16.9

years; but it takes #1 T'1/2=19.4

years to arrive at B, so #2 arrives at B 2.5

years earlier than #1. What is simultaneous

in one frame is not necessarily simultaneous

in another.

QUESTION:

QUESTION:

Hello, I am very interested in how

standing, walking etc in a pool affects the

location your standing center of gravity -

normally just in front of S1-S2. My gut

feeling is that it raises is a tiny bit, but

I'm not at all sure. Do you have the answer?

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

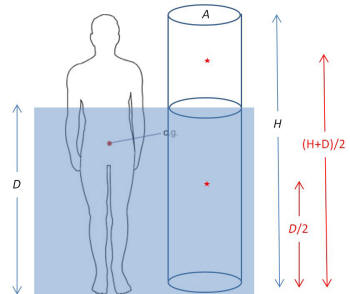

There is, of course, no exact answer to

this question—bodies are different,

distribution of mass is highly nonuniform,

the depth of the water matters, etc.

Center of gravity (cog) is different than

center of mass (com) because com depends on

how mass is distributed whereas cog depends

on how apparent weight is

distributed. Because there is a buoyant

force on the body in the water, his apparent

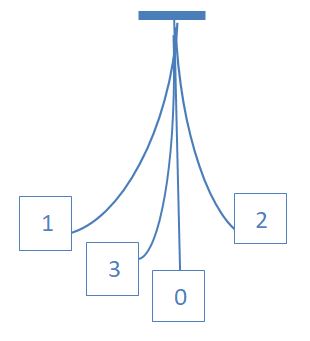

weight of that section is less. The figure

shows a man of height H standing in

water of a depth D. I was a little

surprised to find for the man not in water,

as the questioner implies, that the cog is

near his waist, about H/2; then I

realized that the heaviest bones (legs and

pelvis) are below the waist so this was

reasonable. Being in the middle like this

suggested that the mass is fairly uniformly

distributed so I chose to model the man by a

uniform cylinder of mass M and

volume V=AH; this is a very rough

estimate but is the best I can do and it

will give an order-of-magnitude of how far

the cog will move upward. Before the water

is added the cog of the cylinder is at H/2

and the total weight is Mg where

g=9.8 m/s2 is the

acceleration due to gravity. The total

weight is Mg=ρmanVg,

where ρman=985 kg/m3

is a typical mass density for a man*.

Now let's add the water. The apparent weight

of the submerged part of the cylinder is

W1=(ρwater-ρman)DAg

and the cog is y1=D/2

above the bottom because the mass is assumed

to be uniformly distributed. The weight of

the unsubmerged volume is W2=ρman(H-D)Ag

and its position is at y2=(H+D)/2.

So we can now write the position of the new

cog, ycog=(W1y1+W2y2)/(W1+W2).

The density of water is 997 kg/m3, so ycog=[6D2+493(H2-D2]/[12D+985(H-D)].

As a numerical example I will look at an

H=2 m tall person standing in water of

depth D=1.3 m; this would be

roughly the scale which is in the figure I

have drawn. Doing the arithmetic I find that

ycog=1.63 m. This is

just barely below the cog of the unsubmerged

portion of the cylinder or man which is at

1.65 m. Note that this is by no means a

"tiny bit" as you speculated. The reason for

this is easy to understand—because the

density of water and the density of the man

are so close to each other, the effective

mass of the submerged mass is very nearly

zero.

*As a

touchpoint, a 200 lb man has a mass of about

90 kg, so V=90/985=0.1 m3.

Since V=AH where A is the

area of our model cylinder, A=V/H=0.05

m2.

QUESTION:

QUESTION:

When light moves upward against gravity

it red-shifts (and blue shifts if it were

relected back down). Let's say that the

shift is causes blue visible light to

actually go red. How does this work in a

photonic sense. Do blue photons turn into

red photons? If so, what has happened to the

energy, did it disappear? Energy can't just

disappear, photons have no mass, so it

hasn't become potential energy, where did

the energy go?

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

When you throw a ball straight up in the

air it slows down, eventually stops, and

falls back down. In physics terms, the ball

loses kinetic energy on the way up and gains

it on the way down. Usually we "invent" a

potential energy function and consider it

the result of work done by the gravitational

force, negative work going up, positive work

falling down. In this case the ball's lost

(gained) energy is gained (lost) by the by

the gravitational field. In the case of a

photon, again energy of the photon is lost

on the way up and gained on the way down.

Again, the energy which is lost is gained by

the field and vice versa. A photon

cannot slow down or speed up because that is

a law of nature; its energy is given by

E=hf where h is Planck's

constant and f is the frequency of

the corresponding electromagnetic field of

which the photon is a "member". Thus the

red/blue shifts. To make this a little more

concrete, you probably know that light

cannot escape from a black hole so as it

moves away it eventually disappears

altogether; so the field has gained all the

energy of that photon and this results in

the source of the field, the black hole,

increasing its mass by the amount Δm=hf/c2.

QUESTION:

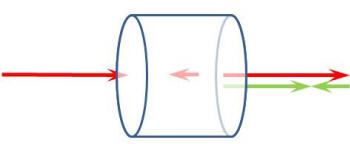

QUESTION:

Hi, my question centres around the

motorcycle community and that “loud pipes

saves lives”. For context if you are not a

biker, the premise is that if your bike is

very loud, you are more likely to be heard

by cars/drivers sooner and therefore

reducing your risk of them not seeing you

and crashing into you. The counter argument

to this is, as the exhausts are at the rear

of the bike the sound is lost out of the

back and therefore they won’t hear you until

you have reached or gone past the car. This

then is further argued that for this to

apply you will need to be travelling faster

than the speed of sound. I believe the

Doppler effect sits in this somewhere too

but I’m not knowledgeable enough to know. So

my question is; Can a motorcycle travelling

down a road at Xmph be heard by a vehicle

ahead of it and at what distance does the

vehicle ahead begin to hear the motorcycle?

I realise there are a number of variables

that would need to be factored in to make

here, (noise inside the car, speed

travelling, etc., but I guess that’s why I’m

asking the question

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

I found a

website where this question was

addressed scientifically, not just

somebody's opinion. I could do no better.

The bottom line is that loud pipes do not

save lives. I might add that loud pipes do

annoy people who value a quiet environment!

I might also add to that gasoline leaf

blowers, lawn mowers, loud cars, etc.

QUESTION:

QUESTION:

If I were travelling at 100mph in a

sealed unit ie a train with no air movement

and I dropped a cricket ball from directly

above a cross marked on the floor, would the

ball hit the cross? As the drop is approx. 8

feet would the result be the same if the

sealed unit/train was 100 feet tall. I

maintain the once the ball has left my hand

it no longer has direct contact with the

movement force and it would very slowly

loose forward momentum as while the

contained air is still moving at 100mph it

would not have the density/power/whatever to

overcome the weight of the cricket ball and

it's forward momentum would gradually

decrease. I ask this as someone says that no

matter from what height the ball was dropped

the forward momentum world remain exactly

100mph and therefore hit the cross. I am 72

and back when I was at school we did not do

this sort of maths(?).

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

This is interesting because it is such a

common gedanken used to demonstrate the

Galilean relativity of two-dimensional

kinematics. But never is it discussed what

the conditions are for it to be absolutely

true. Since the speeds involved are all much

less than the speed of light, I answer this

question considering only Newtonian

classical mechanics. The answer, as I will

show for the real world, is no, even from

8'. The conditions are:

-

The experiment must be performed in an

inertial frame of reference. That is,

the frame of reference must not be

accelerating and we are assuming that

the frame is the train itself.

-

The experiment must be performed in a

uniform gravitational field. The

direction and magnitude of the

gravitational force must be constant in

magnitude every everywhere.

These

are well approximated in the real world as

long as the distances aren't too large.

First, referring to #1, the train is on the

surface of the earth which is a sphere so

the train is moving with some speed v

in a circle which has the radius of the

earth R so it has a centripetal

acceleration v2/R.

But, it is really more complicated than that

because this circular train track is

attached to the earth and the earth is

rotating on its axis. I won't go any

farther, but we could also say that the

earth is revolving around the sun, the sun

is revolving around the center of the

galaxy, etc. ad nauseum. The point

is that the frame of the train is not an

inertial frame; it is an excellent

approximation for most everyday situations.

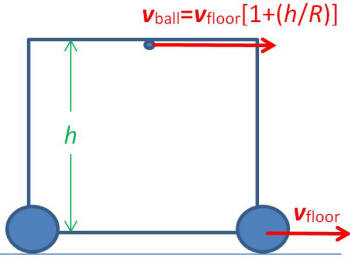

Next

I will give examples of how these two

accelerating frames (circular track and

rotating earth) can affect where the dropped

ball lands. I have drawn a figure which

shows the train car and the ball on the

ceiling, the car being h meters above the

floor. But, if the car is traversing a

circle, the ceiling is moving faster than

the floor as shown in the figure by a factor

of (1+(h/R). The ball will

take some time to fall and during that time

the floor will move forward a distance vfloort

and the ball vfloort(1+(h/R))

so the ball lands vfloorth/R

farther forward than the X initially under

it. Of course for a normal train car h/R

is an incredibly small number and you would

be hard-pressed to observe it. But if you

dropped it from an altitude of R,

the ball would go twice as far as the X on

the floor. A much larger effect, though, is

from the rotation of the earth and is called

the Coriolis force. It is beyond the scope

of this site to get into this force, but the

effect turns out to be that the falling ball

will be deflected in an easterly direction

by the amount d=(ωcosφ/3)√[8h3/g]

where φ is the latitude where the

ball is dropped, ω is the angular

velocity of the earth's rotation (7.27x10-5

s-1), and g is the

acceleration due to gravity (9.8 m/s2).

If you do the calculation for h=100

m, φ=45° you find that d=1.55x10-2

m=1.55 cm. Compare this with the deflection

of the ball dropping from 100 m and the

train going 100 mph=0.028 m/s, d=0.2

mm.

Next

I will give examples of how these two

accelerating frames (circular track and

rotating earth) can affect where the dropped

ball lands. I have drawn a figure which

shows the train car and the ball on the

ceiling, the car being h meters above the

floor. But, if the car is traversing a

circle, the ceiling is moving faster than

the floor as shown in the figure by a factor

of (1+(h/R). The ball will

take some time to fall and during that time

the floor will move forward a distance vfloort

and the ball vfloort(1+(h/R))

so the ball lands vfloorth/R

farther forward than the X initially under

it. Of course for a normal train car h/R

is an incredibly small number and you would

be hard-pressed to observe it. But if you

dropped it from an altitude of R,

the ball would go twice as far as the X on

the floor. A much larger effect, though, is

from the rotation of the earth and is called

the Coriolis force. It is beyond the scope

of this site to get into this force, but the

effect turns out to be that the falling ball

will be deflected in an easterly direction

by the amount d=(ωcosφ/3)√[8h3/g]

where φ is the latitude where the

ball is dropped, ω is the angular

velocity of the earth's rotation (7.27x10-5

s-1), and g is the

acceleration due to gravity (9.8 m/s2).

If you do the calculation for h=100

m, φ=45° you find that d=1.55x10-2

m=1.55 cm. Compare this with the deflection

of the ball dropping from 100 m and the

train going 100 mph=0.028 m/s, d=0.2

mm.

The

central part of your question, "…I

maintain…gradually decrease." is totally

wrong. You, on the train, see the ball with

zero horizontal velocity falling in

perfectly still air. An observer outside

sees the ball with some initial horizontal

speed the same as the horizontal speed of

the air. Air drag will have an effect on the

falling ball, increasing the fall time.

Finally, condition #2 that the experiment

must be conducted in a uniform gravitational

field. This is an exellent approximation

near the surface, but going away from the

earth the field decreases like 1/r2.

I haven't thought about the impact this

would have the falling ball experiment, but

I think I have adequately shown that the

"falling on the X" part is wrong, so I will

save that for another day!

QUESTION:

QUESTION:

In photoelectric effect, why do we deal

with "maximum" kinetic energy?

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

When a photon strikes the surface of

metal it may interact with an electron in

the metal. Suppose that an energy W

is required to remove an electron from the

surface. Then, if a photon of energy E

interacts with an electron on the surface,

the electron is ejected with a kinetic

energy K and the electron will have

a kinetic energy K=E-(E'+W)

where E' is the energy which the

photon has after the interaction. Now,

suppose that the photon gives all

its energy to the electron, E'=0,

and this will be the largest possible

kinetic energy the electron to have, Kmax=E-W.

QUESTION:

QUESTION:

Hello!! I have a question that is

related to space but deals mostly with the

physics of orbital mechanics and free fall

objects. If you were to have a space station

that maintains a constant altitude above a

planet or stellar body, would you still have

gravity? Would that gravity be the same as

the gravity on the surface of the body or

would it be a portion of that gravity?

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

Gravity is a force field which is caused

by the presence of mass. Because it is a

very weak force, a very large amount of mass

is necessary for us to be able to perceive

its presence. It is a field which, if caused

by a massive spherical object (planet, star, etc.), decreases as you get farther

away. Isaac Newton first discovered the

force F on an object of mass m,

a distance r from the center of a

spherical object of mass M and

radius R is F=GMm/r2

where G is a constant. If

d is the altitude, d=r-R, so

r=(R+d) and F=GMm/(R+d)2.

I suppose that answers your questions—yes,

you "would you still have gravity"; no,

gravity would not "…be the same as the

gravity on the surface…" because it

decreases like 1/r2.

There is, however, an important thing to

keep in mind—although there is gravity

there, you would not feel it because when in

orbit you are in free fall as gravity

provides the centripetal force to keep you

in orbit. Discussions of astronauts being

"weightless" when in orbit are

inaccurate—they still have weight but don't

feel it.

QUESTION:

QUESTION:

This is a question that goes (I suppose)

to the fundamental nature of things and for

which you may think me the village

simpleton. But I'll give it a go. Let's

assume a single free photon traveling across

the universe at x frequency. What force,

what principle, what property keeps the

photon locked in its cycle of crest to

trough to crest again? What pulls it back to

center? Why can not it simply "break free"

of this cycle and fly off in a static state

to parts unknown. In other words, why? Why

does energy vibrate at all?

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

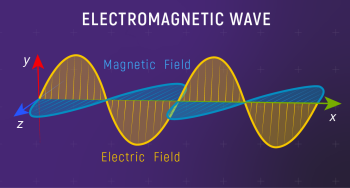

The answers to your questions require

some pretty serious math/physics to answer

rigorously. But I will do my best to try to

give you a more qualitative overview. The

most important thing to keep in mind is that

trying to think of quantum phenomena in

terms of classical phenomena is unreliable

and nothing more than a means of trying to

understand in terms of our everyday

experience. You have some problems with

classical physics as well, so let's start

there.

-

"Why does energy vibrate?" Energy is not

a thing, it is a property which things

have. One kind of energy is kinetic

energy, the energy of motion. If an

object is moving in a straight line, or

spinning, or vibrating it has kinetic

energy; unless something interacts to

take some or all of that energy away, it

will never go away—that's called

conservation of energy. In fact,

the reason energy is useful in physics

is that physicists have defined it so

that it will obey a conservation law for

any "isolated" system. The energy of the

entire universe never changes.

-

"…what…keeps the photon locked in its

cycle [?]…" Think of a vibrating guitar

string: It will vibrate forever because

of energy conservation, right? Of course

not, because it is not an isolated

system. It is vibrating in air and as it

moves through the air the pushes on the

string opposite the direction the string

is moving, slowing it down just like a

wind will push on you. Where did that

energy go? The air, if you had a very

sensitive way to measure its

temperature, would warm up just a tiny

bit. Another way the energy gets lost

(from the string) is that the string is

attached to the bridge which is attached

to the body, so the string gives up some

of its energy to the whole guitar as it

starts vibrating too. But that vibration

sends out sound waves which flow away

carrying more of the enrgy with them. If

you just stretched the string across two

nails on a rod it would vibrate much

longer and you would hardly be able to

hear it because because energy is not

"leaking" to the guitar.

Now, back to the

photon. The first thing is that it is not a

particle or a wave, it is a

particle and a wave. This,

particle/wave duality, is hard to swallow

since there is no really good analogy in

classical physics. If you look for a

particle, you will find a particle; if you

look for a wave, you will find a wave. Just

like an ideal guitar string, it needs

nothing to keep it in its state. A photon is

the tiniest amount of a ray of light that

can exist. It has energy which is

proportional to the frequency of the light

which it is part of. You just get confused

if, as you have done, you try to think of it

vibrating with that frequency. If it is in

empty space and nothing interacts with it,

energy conservation just keeps it moving

along with a certain kinetic energy and

linear momentum (also a conserved quantity).

It has no "static state" and cannot "break

out" without violating energy conservation.

However, if it happened to encounter an

electron it would interact with it and some

of its energy might be given to the

electron.

QUESTION:

QUESTION:

I have a question about defining types

of heat transfer. Me and a friend got into a

debate about wether the so called "radiant"

heat in the concrete floor that has heated

fluid pipes running through it, is in fact

radiant or convection type. Since the

temperature of the air in the room is heated

by this method i say it was convection

occuring. But its always called "radiant"

heat when we have heated slab floors. Is the

heat emitted from this slab in the form of

radiant waves then, or is the parcel of air

itself in contact with the slab heated and

then convects outward via the air itself?

What type of heat are we talking about here?

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

Both play a role in heating the room. If

no air were in the room, the ceiling and

walls would eventually warm up because of

the radiant energy from the floor. But if

there is air in the room, the radiant energy

would heat up the air but not uniformly so

currents of air, convection, would occur.

QUESTION:

QUESTION:

I have a 3.7V and 600mah battery, which

has a big bms that can handle a high current

before rendering a short circuit, but now I

have 2 3.7V and 600mah batteries, the

problem is their bms can't hand alot of

current like the last one, and my device

shuts off when i try it on. so can't I

connect these 2 batteries in parallel with

the bms of the first battery, so the device

doesn't turn off, and it gets a better

battery life time?

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

I don't know anything about battery

management systems (bls) but I do know DC

circuits, so I will take a shot at your

question. For illustration, let's say that

your first battery can handle a current of 3

A and the other two can handle 1 A; suppose

your device draws 3 A. If they all have the

same the same internal resistance and you

connect them, each will have 1 A flowing

through them and two of the three are right

at the limit before they shut off. If,

however, the two have a resistance smaller

than that of the third, they would need to

have more than 1 A and, I presume, the bms

would shut them down.

QUESTION:

QUESTION:

This is a question about sound. If you

were to increase the temperature of a medium

without allowing the volume (of the medium)

to change, how would this affect soundwaves

that travel through it? I've tried

researching this but most of the answers I

get refer to how the change in temperature

changes the density of the medium, which is

not what I am interested in. I want to know

what happens if you prevent the density from

changing. I know such an increase in

temperature would increase the pressure, but

I don't know if that would make the sound

louder or change it at all.

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

This question depends a lot on the

situation you have—is it a gas or liquid or

solid? What is it made of? What is its

molecular structure? But you are lucky if

you want to consider a gas which is well

described by the ideal gas law, PV=NRT.

Volume V is constant, N

measures the amount of gas, also constant,

T is absolute temperature (your

variable), and R=8.31 J/mol·K is

the universal gas constant. The sound has a

frequency which will not change but the

speed v will so the wavelength of

the sound will change. It turns out that the

speed depends only on the temperature and

what the gas is. I will not go through the

whole derivation because it requires a lot

of facility with thermodynamic theory, but I

will give you the final result:

v=√[γRT/M]

where

M is the molecular mass of the gas

and γ is the adiabadic index, the

ratio of the specific heat at constant

pressure to the specific heat at constant

volume, CP/CV.

For example, for air, γ=1.4

and M=0.029 kg/mole, so v=20.03√T.

Don't forget that T must be the

absolute temperature, K. I get v=347

m/s at T=300 K.

QUESTION:

QUESTION:

The Bohr model correctly interpreted the

atomic spectra of the hydrogen atom and

predicted that the excited atom would emit a

photon whose energy is equal to the energy

difference between two specific levels in

the atom.... After that, quantum mechanics

appeared and the Schrödinger equation for

the hydrogen atom was solved Bohr model

becomes incorrect (or inaccurate, or

incomplete) From the Schrödinger equation,

we learned that the electron does not

revolve in a specific orbit around the

nucleus, but its distance from the nucleus

is a potential, that is, it is not a

specific orbit. The question is here: How is

the energy of the photon emitted from the

atom (a specific energy that is responsible

for the distinctive atomic spectrum) equal

to the energy difference between two orbits,

even though the energy of each orbit is

indefinite?? For example, the energy of the

primary orbital in the hydrogen atom,

according to Bohr = 13.6 ev And the energy

of the second orbit = 3.4 ev, so the

difference = 10.2 ev But in the Schrödinger

equation, the electron in the first level

can take energy greater or less than 13.6.

It is true that the average energy in the

Earth's orbit is equal to this value, but

there are possibilities for it to be greater

than even twice this value or less, so how

is the difference between the two levels

always constant = 10.2. This is proven

practically and experimentally through the

atomic spectrum of the hydrogen atom.

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

You have many misconceptions. The Bohr

model is semiclassical and in most respects

just plain wrong. Nevertheless, it played a

very important roll in the development of

modern physics. Just to list a few errors:

-

Electrons are not simply particles.

-

The electrons do not move in circular

orbits.

-

The orbital energies are not determined

by quantizing the angular momentum of

the orbit.

-

The values of the angular moment are

wrong. For example, the ground state has

zero angular momentum so to think it as

an orbit is dead wrong.

-

All states are assumed to be stable so

their decay to lower states is not

explained.

-

It

is empirical and makes sense only in

that it reproduces experimental spectra.

You

have a problem with energies. The zero of

the electric potential of a point charge is

chosen to be infinitely far away. This is

sort of standard of atomic or nuclear

physics. The energy of the ground state is

E=-13.6 eV. Negative energy means

the electron is bound, so 13.6 eV is the

ionization energy, the energy you must

expend to free an electron in this state. In

quantum mechanics we find that the electron

is not a particle but simultaneously a

particle and a wave (wave-particle duality).

The solution of the Schrödinger equation for

the hydrogen atom yields not some orbit for

an electron, but a function (wave function)

which is interpreted as a probability

distribution; for example, for a small

volume ΔV=ΔxΔyΔz

at some point (x,y,z) where the

wave function is Ψ(x,y,z),

Ψ2 is the probability of

finding the electron in that volume. But the

solution has a definite energy (eigenvalue)

for each state, not an indeterminate energy

as you seem to think. Finally, quantum

mechanics gives us the uncertainty

principle: certain pairs of observable

quantities can't be known to arbitrary

accuracy. The pair of interest to us is

energy and time—the better you know time,

the less well you know the energy. The

ground state of lives forever and so its

energy is exactly -13.6 eV; but the excited

states have definite lifetimes so their

energies are uncertain. In principle, if you

measure the energy of a line in the hydrogen

spectrum you would find that it has a

spread, the shorter the lifetime the larger

the spread. This spread is very small and

also often swamped by other effects: most

spectra come from tubes where the atoms are

moving very rapidly and you get a spread due

to Doppler shifts of atoms moving toward or

away from you. I have no idea what you are

talking about regarding the earth's orbit.

QUESTION:

QUESTION:

We have an above-ground pool that

contains roughly 8400 gal of water. It's

dimensions are 25ft long x 16ft wide x 52

inches deep. Our question: Is it possible to

hook a garden hose to the bottom drain

outlet of the pool, and get the water to

rise up to the level of the pool edge (52")

and then drain back down into the pool,

*without the aid of a pump*?

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

I was following everything in your

question until I got to "…and then drain

back down into the pool…". I am going to

assume that you want to connect the hose at

the level of the bottom of the pool and fill

the pool that way and that is what I will

answer. The key is that if the pressure of

the hose is less than the pressure at the

bottom of the pool when it is full, it will

not fill. The typical water pressure in a

household is in the range of 40-80 psi, so I

wall assume yours is 60 psi as an example.

The pressure at the surface of your pool

when it is full is atmospheric pressure,

14.7 psi. As you go down into the water the

pressure increases at a rate of 0.0371 psi

per inch. So the pressure at the bottom of

your filled pool is 14.7+52x0.0371=19.3 psi.

This is smaller than 60 psi so you can fill

your pool this way. On the other hand, why

would you want to? It would probably be

faster to fill it from the top because the

rate of flow through the hose is bound to

decrease as the back pressure on it gets

larger as the pool fills.

QUESTION:

QUESTION:

Suppose a compression spring is placed

between two nearby identical bodies in

space. The stiffness and natural length of

the spring are accurately known. The

gravitational attraction between the bodies

then compresses the spring slightly, and the

compressed length allows the bodies’ rest

mass to be estimated. The spring’s

compressed length should be the same for an

observer moving at high speed at right

angles to the spring, so the mass should be

seen to be the same as before. But using SR

the observer knows this observed mass

exceeds its rest mass. The rest mass would

be less than the mass measured in its rest

frame. So how is this consistent with

invariant rest mass?

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

The answer is simple. The spring

constant is not invariant, it depends on

your frame of reference. Related to this is

the realization that force is not really a

useful concept in special relativity.

QUESTION:

QUESTION:

Suppose a rocket flies at high speed

toward a stationary laser and carries

equipment to measure the frequency of the

laser’s light. The speed of the rocket is

known and hence so is the non-relativistic

Doppler shift. After allowing for this shift

the measured frequency of the light should

be slightly blue shifted. This is because

the time rate of the atoms in the rocket

will be slightly reduced due to its high

speed, so in comparison the frequency of the

laser’s atoms will be higher.

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

You are making this too difficult. To

calculate the frequency of the radiation

observed on the rocket you only need to know

the frequency in the laser's rest frame;

the way the radiation was created is

irrelevant. And I do not know why you ever

mention the non-relativistic Doppler shift

because it is incorrect for electromagnetic

radiation. The correct Doppler shift

equation is λrocket/λlaser=√[(1+β)/(1-β)]

where where β=v/c,

v the relative speed and c

the speed of light; this equation has β>0

for the rocket and the laser moving away

from each other. In your case β<0.

For example, if β=-0.7, λrocket/λlaser=0.42,

blue shift.

QUESTION:

QUESTION:

The double slit experiment using a

series of particles raises a question: Why

does the electron or photon gun not shoot

straight? Assuming the gun is positioned

between the two slits, it should just hit

the same point on the barrier every time.

CRT’s had accurate electron guns, why not an

accurate gun for this experiment? Can you

describe the nature of the trajectory

variance? Cyclical, random or something

else?

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

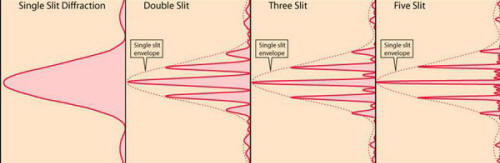

You miss the whole point of double-slit

diffraction. Diffraction happens for waves

but a "pure" particle (if there were such a

thing) does not diffract. Any elementary

particle, e.g., electrons and

photons, are both particle and wave—if you

look for a wave you will find a wave, if you

look for a particle you will find a

particle. This is called wave-particle

duality. If you look for wave behavior of

electrons you need to look for diffraction.

The

rule-of-thumb for whether diffraction is

important is that the slit or obstruction

not be much larger than the wavelength of

the wave. E.g., the wavelength of

light in the middle of the visible spectrum

is about 5x10-7 m; the slits in a

good diffraction grating are spaced by about

5x10-6 m and the diffraction is

easily seen. But what if the slits had been

one meter apart? In that case you would be

hard put to see any diffraction and the

photons could be carefully shot straight

into the gap. There would be single-slit

diffraction from the two slits, but let's

just say they were each a centimeter wide;

if you looked really hard you might find a

little fuzziness of the shadows of the edges

of the slits which would be diffraction.

Now

let's turn to diffraction of electrons. The

wavelength of an electron accelerated by a

voltage of 1 kV (which has a speed of about

1/10 the speed of light) is about 4x10-11

m. So your slits would need to be not too

much bigger than that. But you would not be

able to fabricate slits that close together

because t he

size on an atom is about 10-10 m!

So the pictures you see in text books of

electrons and a double slit are a fraud! No

such slits exist. But that slight-of-hand is

just to get students understand one wave in

terms of some other wave you already

understand without going into all the

technical details of how you can really do

it. There is no doubt that electrons behave

as waves. The first experiment to observe

electron diffraction was the

Davison-Germer experiment; they directed

an electron beam onto an iron crystal, using

the regular spacing of the iron atoms as a

kind of diffraction grating. So, protons,

having much larger mass than electrons, have

much smaller wavelengths. An

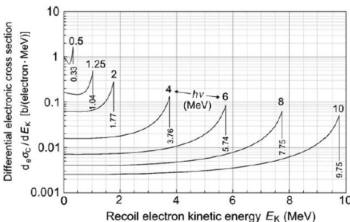

earlier answer showed the results for

800 MeV protons scattering from a 90Zr

nucleus. Protons of this energy have momenta

of about 10-15 m, so to see

diffraction you need a target not too much

larger than that size; the size of nuclei is

about this size. The results are shown in

the graph which shows the intensity of the

proton diffracted from the nucleus. For more

detail, read the answer linked to

here.

he

size on an atom is about 10-10 m!

So the pictures you see in text books of

electrons and a double slit are a fraud! No

such slits exist. But that slight-of-hand is

just to get students understand one wave in

terms of some other wave you already

understand without going into all the

technical details of how you can really do

it. There is no doubt that electrons behave

as waves. The first experiment to observe

electron diffraction was the

Davison-Germer experiment; they directed

an electron beam onto an iron crystal, using

the regular spacing of the iron atoms as a

kind of diffraction grating. So, protons,

having much larger mass than electrons, have

much smaller wavelengths. An

earlier answer showed the results for

800 MeV protons scattering from a 90Zr

nucleus. Protons of this energy have momenta

of about 10-15 m, so to see

diffraction you need a target not too much

larger than that size; the size of nuclei is

about this size. The results are shown in

the graph which shows the intensity of the

proton diffracted from the nucleus. For more

detail, read the answer linked to

here.

This

now answers your question about CRT

electrons not having any problem hitting a

small dot on the screen—the dot is really

huge compared to the electron wavelength.

QUESTION:

QUESTION:

How does touch work from a physical

perspective? From a biological perspective

we know that mechanoreceptors carry impulses

along nerves to the central nervous system.

For examples when my fingers touch the

keyboard of my laptop the mechanical

pressure is converted into electrical

signals sent to my brain and I feel the

keyboard. From a physical perspective one

might argue that we never touch anything.

The cloud of electrons buzzing around the

atomic nuclei comprising the atoms of my

fingertips interacts with the the electrons

of the keyboard, virtual photons convey the

information of the electromagnetic field,

but there is no touching involved. The

electrons do not ”touch” each other. Though

there is no touch involved perhaps we might

say that electrons ”feel” forces (and

accumulate energies from them) whenever

there are electromagnetic fields. My

question is: What is going on at the atomic

level when we touch something? How does the

interaction between the electromagnetic

fields of my electrons and the electrons of

the keyboard turn into an electrical current

strong enough for my brain to detect it?

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

I have recently

answered a question which touched on the

microscopic origin of contact forces. It

turns out that the contact force is mainly

due to a quantum effect, not to

electromagnetic forces between atoms on the

surfaces.

Wikepedia states that "…in quantum

mechanics the Pauli exclusion principle

(PEP) states that two or more identical

particles with half-integer spins (i.e.

fermions) cannot occupy the same quantum

state within a quantum system

simultaneously…". In other words, when two

objects get close enough, the wave functions

of atoms on the surfaces begin to overlap

and the electrons in the atoms begin to be

approaching the same state and atoms on both

surfaces stop getting closer to avoid

violating PEP. It isn't really a force but

the effect is the same—the surfaces push

away from each other. The result will be a

compression just below the surfaces which

will then be detected by the nerves but, not

being a biologist, I couldn't give you any

useful explanation how the nerves

work. Regarding whether the objects actually

"touch" requires, at atomic distances, a

definition of what we mean by touch. I would

say that if wave functions of atoms overlap

that they are touching.

QUESTION:

QUESTION:

I am confused and need help on

understanding forces acting on a car when it

is moving uniformly on a level road. When a

car is moving uniformly (say forward) on a

level road, what is the direction of

friction acting on it? Some say it is to the

left, because some textbooks would describe

the above situation as a having a driving

force pointing forward, and friction

pointing backward. But then I also have read

some online posts, saying that the so-called

"driving force" is actually friction. So the

friction should point forward. Also, I came

across with something called "rolling

resistance". But I am not sure how I could

include it in my understanding. While this

question may seem simple, it really confused

me a lot because I am not sure how much

textbook situations deviate from real life.

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

When you say "…the friction…"

you imply that there is only one frictional

force acting on the car. In the case of a

car going with constant speed on a straight

road, there are three important kinds of

friction acting:

-

The tires are constantly getting

slightly deformed at the bottom and

deforming them requires a force. This is

called rolling friction and is what is

mainly responsible, at low speeds, why,

if nothing is pushing the car, it will

roll to a stop eventually. The road

exerts a force on the tire and the tire

exerts an equal force on the road.

(Newton's third law.) This force acts

backwards.

-

A

second force is static friction which

causes your "driving force" to impart a

forward force on the tire. The mechanics

of your car causes there to be a torque

on your wheels which tries to cause them

to rotate counterclockwise (as seen from

the side). In fact, if the road were

frictionless (icy, for example) the tire

would spin and not cause the car to move

forward. This static friction also keeps

your car from slipping if the road

curves; in that case, the static

friction will have a component in the

direction you are going and a component

toward the center of the curve you are

negotiating.

-

Finally there is air drag which exerts a

force on the car opposite its velocity.

It becomes more important as the speed

increases, increasing quadratically (e.g.

3 times more speed gives 9 times more

drag.)

You

might wonder why static friction could drive

the car forward—the car is certainly not

static. But where the "rubber meets the

road" is certainly static.

I hope

this clears it up for you.

QUESTION:

QUESTION:

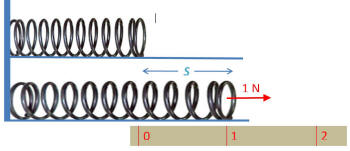

I am in high school and I conducted an

experiment that involved a parallel spring

systems, mass and vertical displacement. The

system had an equivalent spring constant of

around 80N/m. I noticed that a 200g mass

produces close to 0 displacement, but the

difference in displacement in between 1000g

and 1200g is close around 2-3cm. So why does

the increase from 0-200g so insignificant

compared to the increase from 1000g-2000g.

According to hooke's law shouldnt this

similar increase in force result in the same

displacement?

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

The problem here is that Hooke's law is

not really a law, it is an approximation

which works very well in some situations and

not for all situations. For example, suppose

you hung a 1 metric ton mass (1000 kg), a

9800 N weight, from your spring; would you

expect it to stretch 122.5 m? Springs in the

real world are approximately linear for a

limited range of applied forces. If I were

you, I would make more measurements by

adding masses in 200 g (m=0.2 kg) increments

making careful measurements of the stretch

and then plot the stretch as a function of

the weight (W=mg); this should

yield for small masses the slope of the line

is smaller than 80 N/m for small W

but becomes 80 N/m. It might also be

interesting to then take weights off to see

if it traces back on the stretching data; if

it doesn't, that is called hysteresis.

QUESTION:

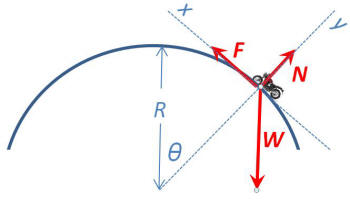

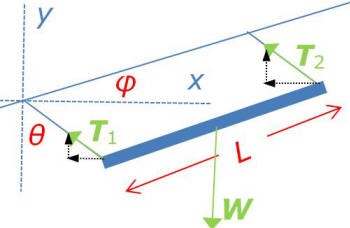

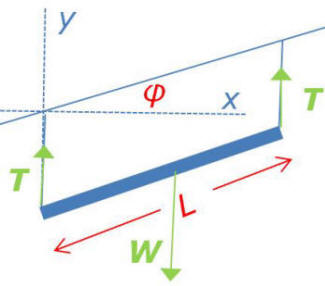

QUESTION:

A motorcycle has to move with a constant

speed on an over-bridge which is in the form

of a circular arc of radius R and has a

total length L. Suppose the motorcycle

starts from the highest point. What maximum

uniform speed can it maintain on the bridge

if it does not lose contact anywhere on the

bridge? My Trouble:- I found the answer in

internet saying the Normal force acting on

motorcycle will be zero. But I am not

getting this part that Why and How will the

Normal force be zero? Isn't Normal force a

repulsive (electrostatic) force between

atoms of two bodies in contact, then why

will it be zero!?

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

First of all, it is not at all helpful

to think of the microscopic origins of

normal forces in classical mechanics

problems like this one. Also, almost every

physics book you will read will say that it

is the result of electromagnetic forces, but

this is incorrect; the origin of this

force is mainly due to quantum effects—the

Pauli exclusion principle—as first shown by

Freeman Dyson. All we need to say is

that when two objects are in contact with

each other there are forces that each exerts

on the other which, by Newton's third law,

are equal and opposite. As is often done

with vectors, it is convenient to resolve

this force into two components, the force

tangent to the surface of contact (usually

called the frictional force F)

and the normal component (usually called the

normal force N).

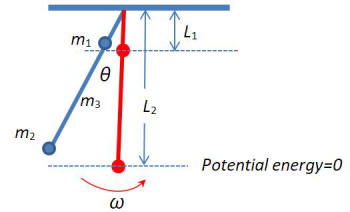

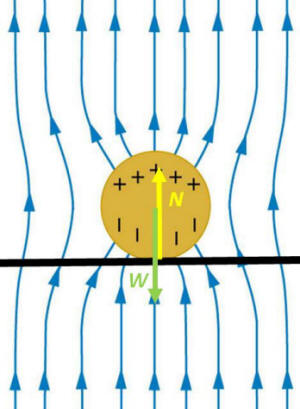

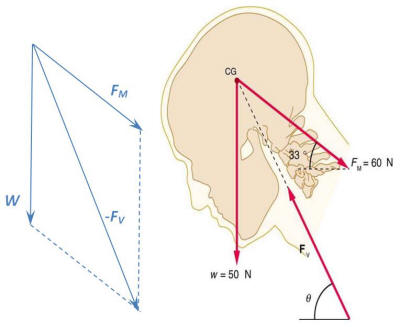

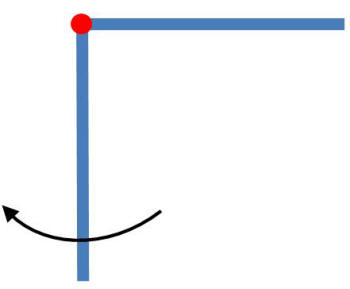

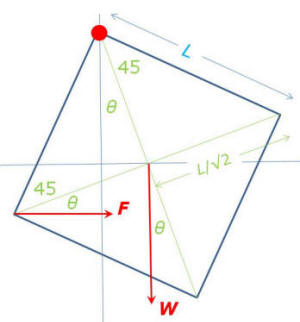

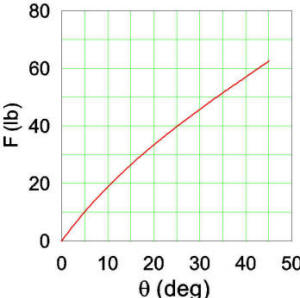

See my figure. So the motorcycle in this

problem has two forces acting on it, its

weight W and the

contact force which has components

F and N.

There is zero acceleration in the x-direction

so

F-Wsinθ=0,

F=mgsinθ.

There

is a centripetal acceleration in the

negative y-direction, ay=-v2/R

-mv2/R=N-Wcosθ,

N=m(gcosθ-v2/R).

Some

things to note:

Some

things to note:

-

Both N and F are

functions of θ.

-

F is positive on the way up but

negative (braking) on the way down. It

is zero at the top.

-

N is always positive.

-

If

gcosθ-v2/R≤0,

N becomes zero or negative; for

a motorcycle, N can't be

negative because this particular contact

force can only push, not pull. This does

not mean that the normal force can never

pull down. What if the road were made of

iron and the motorcycle carried a very

powerful magnet? Also, roller coasters

are not just rolling on wheels but have

to have a mechanism such that if you

were to stop at the top of an inside

loop-the-loop you would not crash to the

ground. What does it mean if N=0?

It means that the motorcycle is no

longer on the road; once N=0

the only force acting on the motorcycle

is its own weight and so it becomes a

projectile; F will disappear

also so its speed will no longer remain

constant; this happens all the time in a

motocross race.

-

For a given angle where N=0,

what is the speed v? v=√(Rgcosθ).

That speed is greatest when when

θ=0°. So we finally come up

with the answer to your question, vmax=√(Rg).

QUESTION:

QUESTION:

I'm finding there are 2 seemingly

contradictory concepts when it comes to air

pressure and temperature. The first is that

when temperature rises, it increase the

pressure of the air because the molecules

move more quickly causing them to hit the

walls of their container more forcefully and

more often. The second is that colder air

has more pressure because the molecules come

closer together, making it more dense which

results in it having higher pressure.

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

The problem is that you are looking too

narrowly. There are other variables besides

pressure P and temperature T.

We should start with the simplest behavior

of a gas, the ideal gas law, PV=NT

where V is the volume of the gas

and N is some measure of the amount

of that gas. Usually, if we want to find the

relation between two of these four

variables, we hold the other two constant.

If we do that for P and T

we obviously find that pressure increases

linearly with temperature, P∝T,

your first "concept," but it should have

been modified by "…if N and V

are held constant…". It is now clear that

your second "concept" cannot also be true

under the same proviso. So let's hold just

N constant (don't add any new air

to V); so now P∝T/V.

So your second "concept" is true only if the

rate which T decreases is smaller

than the rate at which V decreases;

in other words, the pressure will increase

in a cooling gas if the volume is

sufficiently compressed.

QUESTION:

QUESTION:

We are working on a gravity energy

system. How much electrical output (kWs) can

we expect from a 50,000 lbs weight, falling

at a rate of 6 inches per second, and what

the kWs would be if the same 50.000 lbs was

falling at a velocity of 1 foot per second?

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

First, let me be a bit of a scold. A

Watt is a unit of power, energy per unit

time, whereas a Watt-second is a unit of

energy, force times distance. You give me

enough information to tell you the power but

not the energy where I would have to know

the time the weight fell. Also, a Watt is a

Joule per second (J/s) or a Newton-meter per

second (N·m/s); but you use Imperial units

(inches, pounds) so I will have to first

convert these to SI units. End of scold! The

mass of 50,000 lb is m=22,680 kg,

so the weight is 22,680x9.8=2.22x105

N; 1 ft=0.305 m. So, since it falls 0.305 m

in 1 s, the energy per second is 2.22x105x0.305=67.8

kW. So, you could get this much power for

however long as it fell. If it falls for 100

ft, you would deliver this power for 100

seconds, a little less than 2 minutes. Of

course if you correct for friction losses it

would be less than that. But more

importantly, I hope you have a cheap and

easy source to pull it back to the top.

QUESTION:

QUESTION:

I was asked this question many years ago

and passed it on without results: A30 foot

wooden freestanding pole on a concrete

platform is leaning 10 degrees from vertical

and held in place by a wire. The wire

breaks, how many seconds does it take for

the pole to fall to the horizontal ground?

Don’t loose sleep over it. Greetings from

Klaus a 87 yr old forgetful physicist

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

This is basically the simple (physical)

pendulum problem where Newton's second law

results in d2θ/dt2

∝ -sinθ. But you will recall that

this differential equation can only be

approximately solved for θ<<1 and

the solution is the simple harmonic

oscillator. When you and I were students

solutions of the large-angle simple pendulum

were very tedious employing power series or

sometimes obscure special functions. Today

one could write a simple computer program to

solve the equation numerically pretty

easily.

QUESTION:

QUESTION:

If Entangled particles separated over

great distances act simultaneously, then the

"force" binding them must act faster than

light speed? If a particle was on earth and

entangled with a particle in the sun (for

example) then interacting with the earth

based particle would generate an immediate

effect on the sun based particle. But if the

force / energy that binds the two moved at

the speed of light, then it would take 8

minutes for one to impact another, so does

this force move faster than light speed? And

how does this reconcile with Einstein?

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

You at least partially understand why

Einstein referred to entanglement as "spooky

action at a distance". The particles need

not be bound and there is no "force" which

is somehow keeping track of the other

particle. The entangled particles have been

prepared so that they are, in essence, a

single quantum system. Although we would

feel that there was something

"communicating" between the two particles,

it has been proven that whatever it is

cannot be used to send information.

QUESTION:

QUESTION:

Why do 2 spheres hung by a light string

with the same mass but different charges

(+ve) make the same vertical inclination

with the string?

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

Because of Newton's third law: If object

A exerts a force on object B, then object B

exerts an equal and opposite force on object

A.

QUESTION:

QUESTION:

In a rigid body like a coin, if an

impulse is given along its centre of mass

then we calculate the change in momentum by

multiplying mass and velocity change of the

body.then energy is it kinetic energy due to

velocity of its centre of mass. but if

impulse of same magnitude is applied not

along the centre of mass then we get both

linear and angular velocity. But linear

velocity is same as in the first case. But

if we observe the energy then we get both

linear kinetic energy and angular kinetic

energy. How is this possible? How can we get

extra energy without giving more impulse to

the rigid body?

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

This is a little tricky because, as you

state, an impulse of J

causes an increase in kinetic energy, so if

you apply J

anywhere on the body you should get the same

increase in kinetic energy. (I am assuming

no external forces here so we need not worry

about potential inergy.) So, if I apply a

force, the direction of the vector passing

through the center of mass of a rigid body

of mass m, I can write

J=mvcm

where vcm

is the velocity of the center of mass. So

the energy resulting from the impulse is

E=½mvcm2.

In this situation, all energy goes into

translational energy. But if we exert

J elsewhere, it

now also exerts a torque about the center of

mass which causes the object to also acquire

a rotational kinetic energy. Now,

J=mv'cm+Iω/d

where ω is the

angular velocity about the center of mass,

I is the moment of inertial about

the center of mass, and d is the

moment arm of the torque about the center of

mass. I believe this answers your question

because clearly vcm>v'cm

so the translational energy gets smaller. A

very useful theorem of classical mechanics

is that the kinetic energy of a rigid body

is equal to the kinetic energy of

the center of mass plus the kinetic energy

about the center of mass, so

in this case, ½mvcm2=½mv'cm2+½Iω2.

QUESTION:

QUESTION:

is there an equation that could define

the oscillatory motion of a screw as it

rolls down a ramp

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

See an earlier

answer.

QUESTION:

QUESTION:

Hi, I was in my house the other day at

night when I noticed a bizarre light effect

coming through a window sun blind. Looking

across from the hill I live on are street

lamps. When the light of these shined

through the netting I was perceiving what I

could only determine to be an interference

pattern. A point of light was split into 3

definite points. It didn't matter how far

from the netting I was and if I moved my

head side to side the pattern did not

change, the spacing remained specific. I

will be happy to send a video of the

phenomena.

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

The questioner, at my request, sent a

video and a picture illustrating grid size.

I have taken a screen shot of the pattern.

The pattern certainly looks like a

diffraction pattern. But, on closer

inspection, there are some issues. The first

thing that comes to mind is that a

streetlight is normally white light and

seeing a diffraction pattern from white

light is not the familiar pattern of bright

and dark spots because the pattern for a

particular grating depends on the wavelength

of the light so all the wavelengths from

that white light would overlap. On the other

hand, some street lights are sodium-vapor

lamps and sodium has two very close very

bright lines (the sodium D-lines) with

wavelengths a little less than 600 nm=0.6 μ

(microns); this wavelength has a color which

is yellow-orange, and so is the pattern we

are examining. Now, looking at the the

grid-size picture, I would estimate that the

holes are on the order of a quarter of a

millimeter, 0.25 mm=250 μ, with a spacing of

about 0.5 mm=500 μ. There is a general rule

of thumb that for diffraction to be

significant the sizes of the diffracting

object should not be big compared to the

wavelength of the light, and this grid has

features almost three orders of magnitude

bigger than the wavelength of the light if

it is from a sodium lamp. If it is not a

sodium lamp, I have no idea why it is the

color it is. So I have no definitive answer

to the question. My best guess is that the

pattern is simply the pattern of light

passing through the mesh, essentially just

the projection of the mesh pattern and that

the source is a sodium lamp.

ADDED

THOUGHT:

ADDED

THOUGHT:

I was just proofing

this answer before I posted it. The question

included "…A point of light was split into 3

definite points. It didn't matter how far

from the netting I was…". If this was the

case, it is definitely not diffraction which

would spread as you moved farther away. It

was worth doing all the work, though,

because it illustrates how scientists try to see all the angles of a problem,

not just jump to a quick conclusion.

FOLLOWUP

QUESTION:

FOLLOWUP

QUESTION:

Thanks for taking

the time to do a thought experiment on this

puzzling phenomena. I would like to

challenge the concept that it is the grid

mesh projecting through. If this was the

case, then depending on the angle the grid

should move, my hand is not steady in the

video, but the grid pattern does not move.

As the camera pans surely the pattern should

move respectively and the central bright

spot would get split as a fibres moved

across it? The same pattern is present on

both white and yellow sources. Could it

possibly be a diffraction through the actual

strands if they are translucent nylon,

similar to a rainbow diffraction through a

water droplet? I have attached another image

I noticed a couple of days ago, this shows a

window from a long distance away reflecting

sunlight through the mesh. We can see a

splitting of the light into its constituent

colours. Hopefully this adds some useful

information?

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

First, a little correction:

The "rainbow" phenomenon is refraction,

not diffraction; that, in fact, may

be the best clue yet to the final answer to

your question. Let me argue one more time

against diffraction. I think I have done

about as exhaustive an analysis as I can,

given what I have. Maybe if I had a piece of

the material and could do experiments on it

I could learn more. One question: The

pattern—is it ON the mesh itself?

Or can the light be projected on a screen of

some sort? If it is something just on the

mesh, it is not diffraction. If you have

adequate intensity and could get it to

project onto a screen, the pattern would

spread more as the screen got farther from

the mesh. Just to get a better grasp of how

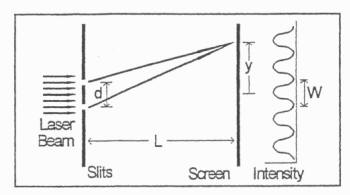

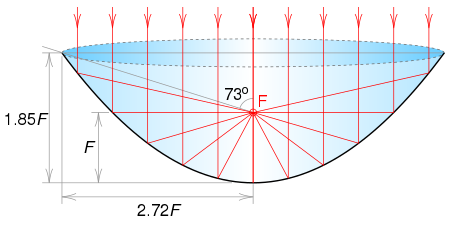

the diffraction can be expected to look we

can compare the spacings W of the

between maxima or minima for a double slit

diffraction pattern, W=λL/d

(see my figure), where λ is

the wavelength of the light, ~0.4-0.7 μ for

visible light. This is just a rough

approximation to spacing we would expect,

but one which an excellent

order-of-magnitude estimate of spacings in

any multiple appatures array. First, it

depends on how far away you put a screen; If

L is 2 m away, the spacing is twice

what it is when L=1 m. Taking a

typical visible wavelength to be 0.5 μ,

W=0.5x1/500=1 mm at L=1 m.

Somewhat to surprise, this is not at odds

with your observation. But it is not

definitive because the spots must get

farther apart as you move away from the

mesh. If you find that the spacing remains

the same, relative to the grid, regardless

of the distance you are from the grid, it is

not diffraction. I do like your idea that

perhaps refractions of the light passing

through translucent fibers is responsible.

So I guess I still stick with my original

conclusion about what we are seeing.

QUESTION:

QUESTION:

Let we have the result of a physical

measurment like this: "Experiments have

Dirac’s number at 1.00115965221 with an

uncertainty of about 4 in the last digit" Is

this gives any interval that we could say

certainly Dirac's number is within it? I

mean exact certainty like 3<π<4. If

so what is smallest such an interval?

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

The answer to your question hangs on

what you mean by "about 4". Normally we

would say what your question says but

without the 'about' which would be denoted

by 1.00115965221(4) or

1.00115965221±0.00000000004. But the "about"

indicates that there is uncertainty in the

uncertainty, and I don't really know how to

notate that.

QUESTION:

QUESTION:

Does it require more nuclei to fuse the

heavier elements and is it the reason for

why the heavier elements are more rare?. For

example it takes 4 hydrogen nuclei to make

one helium nuclei so it takes more helium

nuclei to create the next element.

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

It is not fruitful to think of fusion as

how many nuclei are fused to make a

particular nucleus because there are so many

ways any element could be made by fusion

reactions. For example, you could make

12C by fusing two 6Li or

three 4He. What needs to be

considered is the energetics of fusion, can

you make a new nucleus by fusing lighter

nuclei? At the beginning of the existence of

the universe there was almost nothing but

hydrogen, a little helium, maybe a bit of

lithium. Now, if enough of these primordial

elements become bound by gravity, they will

eventually collapse to the point where

fusion ignites and you have a star. Why do

stars shine and get very hot? Because fusion

results in huge amounts of energy being

released as it happens. As the star gets

older and older the average nucleus is

getting heavier and heavier. But now there

is a "barrier" for this process to continue

forever until you have one giant nucleus: it

turns out that when you reach iron, fusion

happens only if you add energy, that is it

is no longer a source of energy when heavier

nuclei fuse. So the earliest stars had

almost no elements in them heavier than

iron. Then why are there elements heavier

than iron in the universe? It is because

when the a star is near the end of its life

it ends with a terrific bang called a nova

which creates an enormous energy which

forces fusion to continue as the star is

exploding creating many new elements. After

the nova, all the debris along with hydrogen

clouds coalesce and make new stars and those

stars have heavier stuff like lead and gold

and silver etc. in them. This is

why Carl Sagan liked to say "We are all made

of star dust".

QUESTION:

QUESTION:

Why is Chernobyl still a toxic wasteland

and Heroshima and Nagasaki populated and

safe today?

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

An atomic bomb and a reactor meltdown

are very different events. A bomb carries a

relatively small amount of fissile

materials. For example, Fat Man, the

Nagasaki bomb had about 14 lb. of

plutonium-239; about 2 lb. actually

fissioned in the explosion. Since long-lived

radioactive isotopes from the bomb come from

those two pounds, there is not really all

that much. Furthermore, that bomb was

detonated at 1650 feet altitude, the

radioactive fission products would have been

spread over a pretty large area. Most of the

casualties were due to burns, pressure

burst, flying debris, collapsing walls and

roofs, etc.; only those in a relatively

small area directly under the explosion were

injured of killed because of direct

radiation (gamma rays, x rays, neutrons).

A

large nuclear reactor like at Chernobyl has

a core of about 100 metric tons of uranium

when first installed and as that uranium is

used up it is converted to many radioactive

isotopes, both short-lived and long-lived,

which are still confined in the cylinders

the core is composed of and highly

radioactive. At Chernobyl a combination of

human error, design faults, and mechanical

failures caused the core to overheat, the

resulting steam at too high a pressure to be

contained, and the steam containment

exploded sending out huge amounts of

radioactive steam to escape. Since the water

also cools the core, the core overheated,

burned, and melted and the explosions spread

all the nuclear waste over the adjacent

land. A whole different order-of-magnitude

from a bomb.

A

large nuclear reactor like at Chernobyl has

a core of about 100 metric tons of uranium

when first installed and as that uranium is

used up it is converted to many radioactive

isotopes, both short-lived and long-lived,

which are still confined in the cylinders

the core is composed of and highly

radioactive. At Chernobyl a combination of

human error, design faults, and mechanical

failures caused the core to overheat, the

resulting steam at too high a pressure to be

contained, and the steam containment

exploded sending out huge amounts of

radioactive steam to escape. Since the water

also cools the core, the core overheated,

burned, and melted and the explosions spread

all the nuclear waste over the adjacent

land. A whole different order-of-magnitude

from a bomb.

QUESTION:

QUESTION:

Does it require more nuclei to fuse the

heavier elements and is it the reason for

why the heavier elements are more rare?. For

example it takes 4 hydrogen nuclei to make

one helium nuclei so it takes more helium

nuclei to create the next element.

ANSWER:

ANSWER:

It is not fruitful to think of fusion as

how many nuclei are fused to make a

particular nucleus because there are so many

ways any element could be made by fusion

reactions. For example, you could make

12C by fusing two 6Li or

three 4He. What needs to be

considered is the energetics of fusion, can

you make a new nucleus by fusing lighter